Seven myths about sex education debunked

Countries with more sex ed have lower teen pregnancy rates, yet policymakers in Kenya continue to push against it.

Imagine firefighters approaching a burning dormitory and being asked: “Won’t that water encourage the students to start fires?”

This is essentially what happens when sex education is proposed as a way to reduce teenage pregnancies in Kenya. This conversation was revived earlier this year when it was reported that 4,000 teenagers had become pregnant in five months in Machakos county. This news sparked a public outcry, but the numbers were not unusual. The country records around 400,000 teenage pregnancies each year.

Nonetheless, the debate about how to reduce teen pregnancies returned to the fore. And, once again, Kenya’s decision-makers expressed their suspicion of sex education as a potential fix. Education Minister George Magoha even asked openly: “Could some NGOs who are keen on pushing sex education be using these exaggerated numbers?”

Kenya’s school curriculum does contain some sex ed. But while UNESCO recommends teaching the subject from when children are five years old, Kenyan schools only begin teaching it when students are already teenagers. The subject is tucked under Life Skills Education and not examinable. It is so under- or mis-taught that a 2017 evaluation found only 2% of students had learnt it fully.

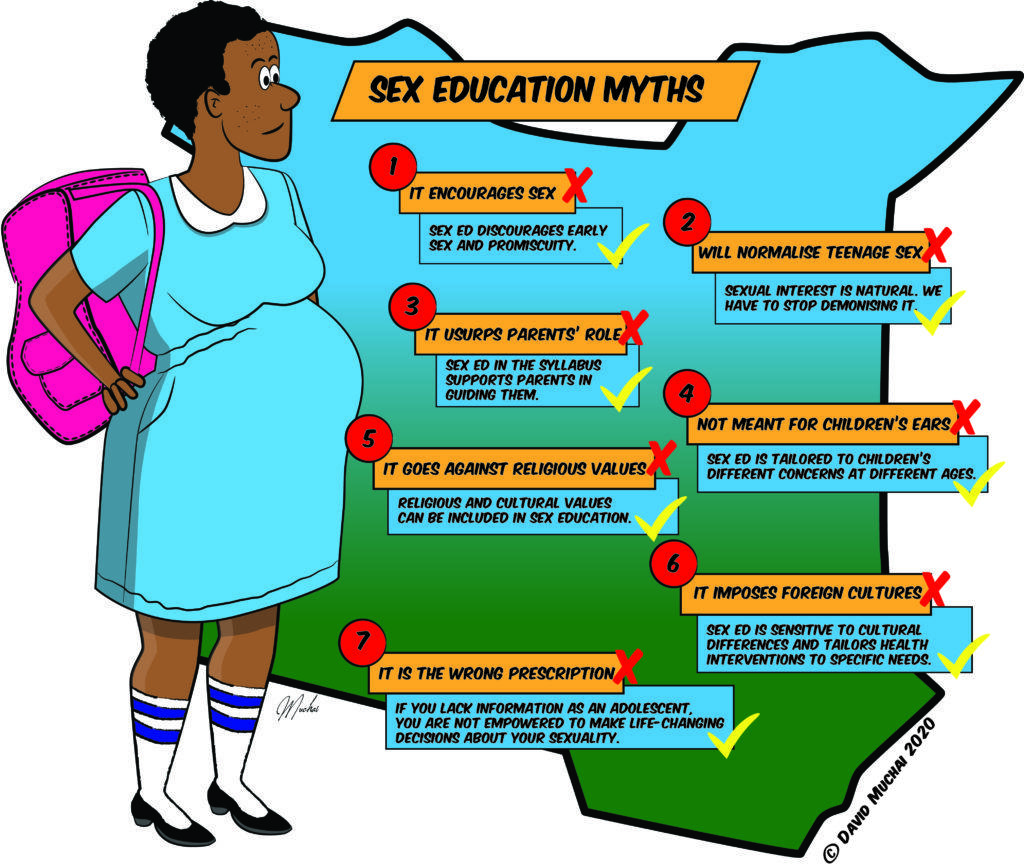

The reasons that governments object to sex ed — or comprehensive sexuality education (CSE) — can be summed up in seven criticisms, which have been voiced by parents, teachers, politicians and religious leaders. These are listed and dissected below.

1) It encourages sex

This position was well summed up by Wilson Sossion, secretary general of the Kenya National Union of Teachers (KNUT), who said: “There’s no way you can give a child physical education uniform and you don’t allow that child to do physical exercise”.

Critics suggest sex ed will encourage children to have sex, yet research suggests the opposite is true. A study by the Guttmacher Institute found that “there is now clear evidence that sexuality education programmes can help young people to delay sexual activity.” A UNESCO report found children who are taught CSE tend to have less sex, fewer sexual partners and reduced sexual risk-taking.

In any case, the modern world is already saturated with sex and Kenyan teenagers are at it. As Jolly Mukangu from Reproductive Health Services Nairobi told this writer: “We need to stop burying our heads in the sand.”

2) It normalises teenage sex

In Kenya, children are brought up to view sex as a dirty word. It is believed that speaking about it openly will normalise it among teenagers. It is this attitude that limits CSE and likely contributes to Kenya’s teenage birth rate of 74 per thousand.

Societies in some countries take the opposite strategy. They talk about sex as a normal and healthy act, opening the door to frank education so children don’t need to find things out themselves the hard way. It is these countries that typically have the lowest teenage pregnancy rates. Switzerland, for instance, has just 3 teen births per thousand.

It is difficult to compare rates across countries with different norms around when women give birth, but as Rev Pete Odera said: “Children will always be interested in sex. We have to stop demonising it. It’s a natural thing.”

3) It usurps parents’ role

Some people suggest that it is the role and responsibility of parents, not the government, to educate their children about sex. But in Kenyan society, parents typically avoid talking to their kids about sex. Traditionally, that role was entrusted to aunts, uncles and grandparents. And even if parents were willing to talk sex with their children, it is likely they would — like parents in a UK study — “feel embarrassed, uncomfortable and have neither the skills nor the knowledge to do so”.

There are some courses in Kenya that help parents and teenagers have conversations about sex, but they are the exception. Parents are not educating their children about sex. The only way to ensure all children get the right information is to make it part of the school syllabus.

4) It’s not meant for children’s ears

When a bill proposing sex ed from age 10 was put forward in 2014, many parents asked for it be raised to 14 before the bill was eventually shot down. Many parents and teachers believe it is premature to talk to children about sex.

However, as family therapist Michael Ungar noted: “The parents who are most hesitant to let their children hear the truth about sex have children who are the most at risk of becoming victims of abuse, or unintentionally causing, or having, an unwanted pregnancy.” Sex ed sensitises kids to their body parts and teaches them what is appropriate and not. It prepares them to recognise potential abuse by adults.

Besides, sex education is not just about sex. A five-year-old may be wondering, “Why does he have a penis and I don’t?” A 12-year-old: “Why am I bleeding and she is not?” A 15-year-old: “Why do I get butterflies in my stomach when I see so-and-so?” CSE is tailored to their different concerns at different ages.

5) It goes against religious values

Some people argue that sex before marriage is a sin, so the only thing children should be taught about sex is abstinence. Studies in the US, however, suggest that abstinence-only programmes do not reduce teenage pregnancies. Moreover, they leave children uninformed about the risks of sex and sexually transmitted infections.

CSE does, in fact, teach abstinence. But it also covers the “what if”. It recognises that premarital sex happens. In Kenya, for instance, 47% of teenagers are sexually active before turning 18, the local age of consent. Rather than seeing sex ed as inherently anti-religious, conservative voices can be brought into the planning process, as the UN Population Fund tried in 2016.

6) It imposes foreign cultures

In conversations about CSE, some critics have raised fears that it will lead to behaviours that they deem to be foreign and unwelcome in their societies. Putting aside the value of that argument, one of the principles of sex ed is that it is culturally appropriate. For instance, Senegal, Nigeria and Mozambique have rebranded CSE as “family life education” to make it more acceptable and have omitted sensitive topics such as abortion, homosexuality and masturbation. These gaps limit the efficacy of sex ed, but some CSE is better than none.

Making sex ed culturally appropriate is also not just about leaving some things out, but also about making sure certain topics are included. In Kenya, many of the biggest threats to sexual and reproductive health — such as FGM, early marriage and male shame around sexual abuse — derive from local cultures.

7) It is the wrong prescription

In the recent controversy around teen pregnancies, some called for a ban on porn sites or blamed explicit song lyrics as the root of the problem. Psychologists have explained, however, that mere censorship is futile. Rather than trying to stop children hearing or seeing certain content, it is more important to educate them on the reality and on how to make sense of such information.

The way forward

Kenya’s government has tried to tackle teenage pregnancies through a new National Campaign against Teenage Pregnancies and by bolstering efforts to combat sexual abuse. It is now time to give comprehensive sexuality education a chance, too. The reasons not to simply don’t hold water.