The most worrying aspect of the Kankara kidnapping

Could Boko Haram’s spread in northwest Nigeria increase opportunities for coordination between Islamist groups in the Lake Chad Basin and Sahel?

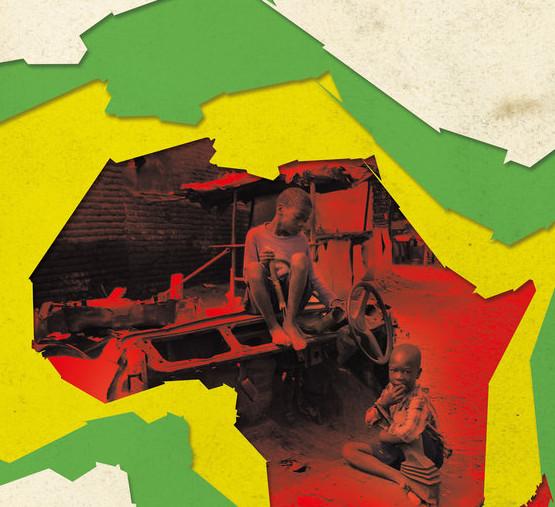

Outside Kurmi Market in Kano, northwest Nigeria. Credit: Eugene Kim.

On 17 December, 344 schoolboys who had been abducted from their school dormitory in northwest Nigeria were suddenly released after six days in captivity. We saw emotional scenes of parents weeping as they hugged their little ones. Nigerians collectively sighed with relief.

However, the involvement of Boko Haram in the kidnapping is a reason for continued concern across the region. Since 2009, the Islamist militant group has killed an estimated 37,500 people, displaced over 2 million. It has mostly operated in northeast Nigeria, but also around the Lake Chad basin in Niger, Chad, and Cameroon.

Its emergence in Nigeria’s northwest – what would be new territory for it – is a worrying sign and was corroborated by Nigerian intelligence agencies and the US Special Operations Command in Africa in August 2020. There are indications that the Boko Haram faction led by Abubakar Shekau as well as those allied to al-Qaeda and the so-called Islamic State (IS) are all seeking to consolidate their presence in northwest Nigeria.

Some militants have reportedly formed an alliance with criminal gangs there. Locally referred to as “bandits”, these groups have killed over 8,000 people in the last decade and robbed or extorted millions of dollars in ransom payments. Mass kidnapping had not been part of their modus operandi until now.

Through partnering with Boko Haram, gangs stand to gain a moral justification for their crimes by framing their actions as part of a jihad approved by Allah and their gains as booty of war permitted by Islam. This may make them more vicious and allow them to recruit more young people. Meanwhile, by expanding into the northwest, Boko Haram factions achieve both an ideological victory by growing its “caliphate” and may find opportunities for boosted income through access to gold mining and agricultural industries and more opportunities for its burgeoning kidnap-for-ransom economy.

The most troubling aspect of Boko Haram’s expansion to the northwest, however, is that it could connect two crisis zones in which Islamist militant groups operate. Northwest Nigeria lies between Boko Haram’s epicentre in the vast marshy land of the Lake Chad Basin and the semi-arid regions of Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger in the Sahel.

An Islamist land bridge in West Africa raises a number of concerns for governments with interests in the region and questions about the potential for alliances between the Sahelian and Lake Chadian groups.

It is unlikely that the Shekau faction, which claimed responsibility for the abduction of the boys and has the second largest operation of the Boko Haram factions, will collaborate with the Sahelian groups. While an active member of the global jihadi movement, Shekau has always fought fiercely to retain his independence from both IS and al-Qaeda – something he has at times struggled to do. There is, however, a strong potential for practical alliances to be forged between the other two factions of Boko Haram. They both have affiliations with IS or al-Qaeda and already, at least in terms of propaganda, support their counterparts in the Sahel. The Islamic State West Africa Province, the largest Boko Haram faction, has also developed its presence in the north-west and could expand its collaboration with IS in the Greater Sahara. Ansaru, which is based in the north west, also has an established affiliation with al-Qaeda.

Urgent action

Tackling this development will require urgent action. To begin with, the Nigerian government will need to come to terms with the fact that Boko Haram is far from defeated in the northeast and that it is expanding into other parts of Nigeria. Downplaying the link between Boko Haram and criminal groups in the northwest is dangerous and will only allow these violent groups to consolidate their new alliance and commit more heinous attacks.

The Nigerian government also needs to bolster its military, security, and intelligence cooperation with neighbouring countries. Boko Haram’s spread constitutes a deepening transnational threat that requires a response from governments in neighbouring states and beyond. The multinational joint task force consisting of soldiers from Nigeria, Niger, Cameroon, and Chad that operates around Lake Chad needs to be strengthened. Furthermore, Nigeria needs to consider pursuing bilateral military and intelligence cooperation with Niger to fight the groups in the northwest.

Western governments and partners supporting West African countries in the fight against terrorism should treat the northwest as a new frontier of jihadism. They should update their policy of seeing the Sahelian crisis as distinct from the Lake Chad region as the lines are increasingly blurred.

Military support will be necessary, but cooperation must go beyond this. Military efforts can only contain the violence. They cannot address the root causes on which violent groups thrive. Governments and their partners must therefore work to strengthen the social contract with their citizens. They must address poverty and inequality, provide education and create jobs, build infrastructure and confront the perverse interpretation of Islam extremist groups peddle.

The Kankara kidnapping has provided an unmistakable signal to the Nigerian government and their partners that must now grasp the long-term challenge that Boko Haram represents. Only a localised holistic approach will have a chance of succeeding.

Correction [17/2/21]: The article originally stated that Shekau’s faction was the largest and ISWAP second largest. This has now been corrected.

[…] has not stopped Nigeria’s jihadists from attempting to benefit from the instability. There is growing evidence that jihadists have been in contact with bandits to make inroads into the Muslim-majority […]