Debating Ideas is a new section that aims to reflect the values and editorial ethos of the African Arguments book series, publishing engaged, often radical, scholarship, original and activist writing from within the African continent and beyond. It will offer debates and engagements, contexts and controversies, and reviews and responses flowing from the African Arguments books.

Sitting in my living room in Johannesburg watching Brian Kandoro, a Harare-based stand-up comedian, perform his show ‘Conspiracy Theories’ on YouTube. My body had a visceral reaction to his disregard for the ‘rules’ of public talk that I learned and internalized growing up in Zimbabwe. His show was performed last year in Harare, Zimbabwe, and he jokes openly about the country’s feared Central Intelligence Organization (CIO) agents and audience members that could be beaten up. When I was growing up in the 1990s, you could not talk about CIOs and disappearing openly like that, especially not on a stage in front of so many people. I cannot help the fear I feel and especially as I think about his safety and wonder how the audience felt. Did any of them have the same reactions as mine, I wonder?

In this blog, I want to explore the ways in which traumatic memory of violence which happened in Zimbabwe has travelled across space and time, from Zimbabwe to South Africa, the country where I currently live. In particular, events that happened in the 1980s in Zimbabwe are being remembered and carry currency in Zimbabwean migrants’ contemporary lives in Johannesburg. Furthermore the memory is being transmitted across generations in different ways.

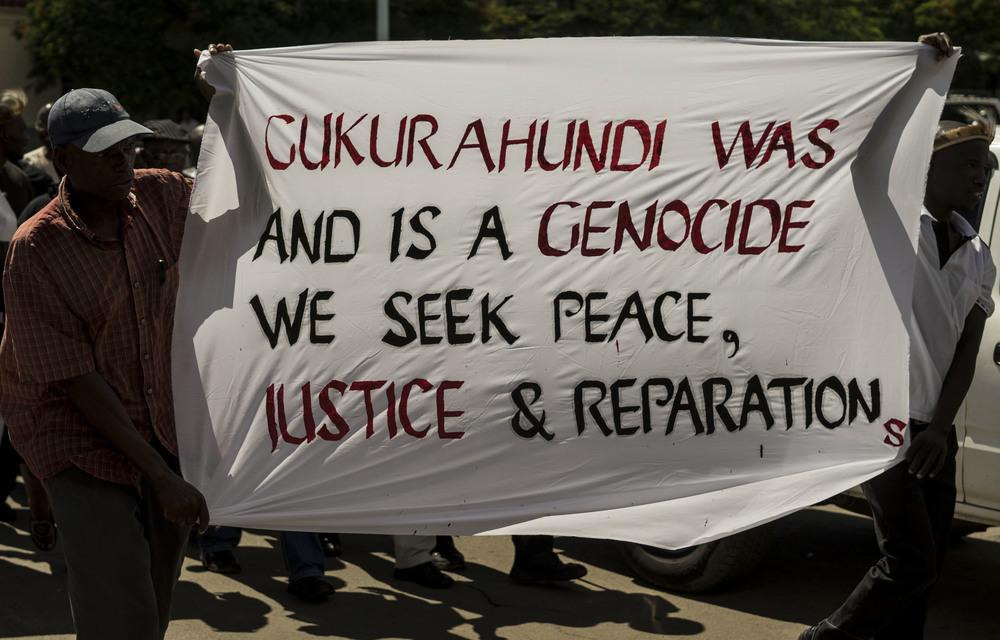

I have an intimate, first-hand knowledge of this. I grew up in Zimbabwe with the story about the Gukurahundi that I heard from my grandmother. My parents also had first hand experiences of the violence but I only learned about these when I began my research after I had moved to South Africa in 2006. Living in Zimbabwe like many other victims my parents did not speak openly of their experiences. Gukurahundi was state-sponsored violence that occurred soon after Zimbabwe achieved independence in 1980, when the army unleashed a torrent of repression on citizens under the guise of stemming out dissident activity. The areas targeted also happened to be strongholds of the main political opposition party at the time. Political alliances of the day fell along ethnic lines and mostly the ‘Ndebele’[1] were affected. While the violence ended in 1987 with the government declaring amnesty for everyone involved, there was no official acknowledgement of the atrocities, the lives which were lost and the damage caused to the affected areas including their underdevelopment.

My grandmother lost her sight, hearing and sense of smell after being beaten by soldiers during Gukurahundi. Her story never named the violence but referred to it as ‘that time’. In Johannesburg I found a more open story sometimes in songs during community meetings which explicitly named the Gukurahundi and its effects on the singers. I became curious about this shift in the way Gukurahundi was being remembered in Johannesburg, and the differences that existed between how my grandmother told her story of it and that of the singers’ remembrances.

Over the years the meaning attached to the violence varies. Some see it to have been a political strategy to consolidate power soon after independence. There are those who see the violence as ethnic cleansing, a genocide aimed at removing the Ndebele to create a pure Shona Zimbabwean nation. In Zimbabwe during Robert Mugabe’s presidency, speaking about the violence was branded as sowing the seeds of ethnic division. Those who went against this faced imprisonment. The artist, Owen Maseko’s exhibition, for example, which commemorated the events was quickly closed and Maseko was arrested. When the incumbent President Emmerson Mnangagwa came into power, he made promises of opening up dialogue about the violence. However the commission that was set up was challenged by communities and not seen as a genuine attempt at dealing with the issue. Additionally, for many of the victims of the violence President Mnangagwa bears guilt of the atrocities as he was the Minister of State Security during the violent period. As such for many, the perpetrator remains in power today as when Robert Mugabe was in power.

My interest in these issues inspired me to conduct PhD research. Initially, I intended to carry out a comparative study on how the memories and stories of Gukurahundi differed between those living in Zimbabwe and South Africa. In 2010, I returned to Zimbabwe while making plans to begin my PhD fieldwork. I remember chatting to a friend about my research ideas as we sat in a restaurant, a public place. She immediately looked around, told me to lower my voice and to forget about doing such a study in Zimbabwe. Not right now anyway, she concluded. As someone who had, by then, lived in South Africa for a considerable time it shocked me that I had lost that art of being Zimbabwean, the personal censoring to avoid being targeted by the government security personnel. Whether this was based on a real threat to my life or imagined, I had learned not to speak openly about such sensitive topics. Actually, I had learned not to speak about such topics at all. It is almost ten years later now as I was watching Brian Kandoro, I realized I had not lost all of it. My body carried the memories and I was responding in the way it had learned to.

I proceeded with fieldwork in Johannesburg. ‘Gukurahundi is alive and living in us’, one of the Johannesburg-based research participants said. The memories of Gukurahundi have followed the migrants’ trajectories showing the complexity of memory and its transmission across space and time. In Johannesburg many celebrate the relative freedom to speak about their experiences but continue to live in fear of the rumoured presence of undercover Zimbabwean state agencies. Are they imagined or real? It remains to be proven. However, these rumours structure how people live their lives even in Johannesburg. I may have been too young to remember the Gukurahundi, but I have vivid memories of the late opposition leader, Morgan Tsvangirai’s swollen eyes and bloody clothes after he was arrested in 2006 – emblematic of the violence that ZANU(PF) unleashed against the Movement for Democratic Change (MDC). What are the effects of living in this kind of state for citizens? What is the heritage of growing up in Zimbabwe and living with state terror? Furthermore, trauma can be transmitted. Kaethe Weingarten has shown how trauma from political violence can be passed onto future generations. Using epigenetics, Rudahidwa et al. demonstrate this in the African context in a study of Rwandan genocide survivors and their children. Vamik Volkan further argues that second generation victims may claim the role of correcting the wrongs of the past. In the case of the Gukurahundi, second generation victims, those who witnessed the violation of their parents or heard the stories have been mobilized to correct the wrong in varying ways, as my own research has shown.

Some victims of Gukurahundi have argued that state acknowledgement of Gukurahundi is foundational in building a Zimbabwean nation that is in any way inclusive of the victims of Gukurahundi. Yet there are others, who are calling for the cessation of western Zimbabwe and the forming of a separate nation for victims. What does this all mean for Zimbabwean politics and the building of a nation going forward? Recently the cessation debates for the creation of a separate nation seem to be the most viable option for many. The idea of a Zimbabwe where victims of the Gukurahundi are included seems to be losing currency. However, there are others who are not in those extreme ends of the continuum of possibilities. For example on Twitter I have found @Mamoxn uses the hashtag #ZANUPFmustgo in all her tweets. A woman from the Matabeleland parts of the nation who has chosen to speak as a Zimbabwean and claim her activist role and place in changing Zimbabwe.

Watching Brian Kandoro after many years of living outside of Zimbabwe. I wonder if these feelings I carry will be or have already been passed on to my children who have never lived in Zimbabwe. What does it mean for the children born in the diaspora and for the memories that people have carried and are passing onto future generations? The Gukurahundi violence remains a history without any official acknowledgment of its impact or its intent and purpose. Its memory and trauma are being transmitted and some are preoccupied with telling the story of the Gukurahundi to break this silence and seek acknowledgement of the atrocities. This is important for healing; however, it is not any just form of remembering and it is possible, as I found in my research, that acknowledgement may in turn silence and leave out some victims from the healing it aims to bring. Careful consideration is needed to find answers to the question: what is the appropriate storying of the atrocities for healing?

Endnote

[1] Ndebele here is used as a regional political identity that has other ethnic identities subsumed under it. There is contestation as to who is Ndebele, however here, it is used in reference to victims of the Gukurahundi.

[…] Source link : https://africanarguments.org/2021/05/violence-and-generational-trauma-gukurahundi-memo… Author : Duduzile Ndlovu Publish date : 2021-05-26 11:22:58 Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source. Tags: GenerationalGukurahundimemoryTodayTraumaviolence Previous Post […]