Debating Ideas aims to reflect the values and editorial ethos of the African Arguments book series. It offers debates and engagements, contexts and controversies, and reviews and responses flowing from the African Arguments books.

This is an abridged version of a discussion with the Kenyan human rights activist and community organizer, Gacheke Gachihi. Gacheke is currently the coordinator of the Mathare Social Justice Centre in Nairobi, which is a grassroots organization that has led campaigns against police brutality. In our conversation, we discussed the social and economic impact of Covid-19 on Kenya’s urban poor; extrajudicial killings within the country; the international protest movement for racial justice and police reform; and Kenya’s upcoming 2022 presidential election.

Gacheke Gachihi at an Amnesty event

LM: I wanted to start the interview by discussing your own political history as an activist in Kenya. You first arrived in Nairobi in the early 1990s. Where in Kenya where you born and raised and what were the circumstances that took you to Nairobi in the first place?

GG: You know I am the younger generation of the Kikuyu community that was taken to Rift Valley by the British colonial settlement. My grandfather was taken there in the early 1920s. That’s where I was born, and I grew up in Rift Valley. In my early childhood, I did a lot of work cultivating the forest land in a place called Kericho. In 1987, we were expelled from the forest. In 1992, the Rift Valley was a political hotbed for the Moi administration. As a Kikuyu, who was living in those areas, bordering other ethnic communities, when the violence erupted, we left there. That’s when I arrived in Nairobi in 1993, which exposed me to the difficulty of life in a city: police brutality, arrested all the time because they would say we were doing illegal car washing. This ushered me to the struggle for human rights.

LM: When I met you in 2013 in Nairobi, you were working as a leader within the social movement Bunge La Mwananchi, or the People’s Parliament. Can you tell me a little bit about the history and politics of this movement? What types of political work have they carried out within Nairobi and Kenya more broadly?

GG: Bunge la Mwananchi, we can call it People’s Parliament. It basically started in a park in Jeevanjee Gardens [in Nairobi]. When democratic space started opening in 1990, people started having open space, where they would air their debates. That’s how personally I started visiting some of the debates. From there, I became a member and we progressed and formalized. We did some campaigns around the debates that we were having at the park. Like one campaign called Unga Revolution [which aimed to bring down the price of Unga, or maize flour]. This had a very major political impact and even the national political class appropriated some of our ideas.

The best thing with Bunge is that it acquired a very powerful identity. [Kenyan] politics is organized ethnically. Bunge was not ethnic. It was different communities coming together. Different class formations from the slums, from the middle class, meeting in the park. Although not formalized in a registered organization, it was a space that created a powerful platform for the emergence of many grassroots political activists that today are providing leadership in the social justice movement that is shaping up now in Kenya, both in urban and rural areas.

People’s Parliament in session at Jeevanjee Gardens, Nairobi

LM: At this point in your career, after almost three decades of activism, how would you describe your own political beliefs today?

GG: My consciousness evolved because of exposure to poverty and the violence of the neocolonial state. I became conscious first as a strong human rights activist and then I broadened my vision of social justice and that’s where I am. I believe that if you have a democratic state in Kenya founded on social justice and human rights than we can mitigate the crisis that we are facing with the neoliberal economy and the neocolonial state that is becoming very strong with poverty, unemployment, violence, drugs and crime.

LM: Much of your political work has been focused on one of Nairobi’s largest informal settlements, Mathare. Can you describe Mathare for those who have never been to Nairobi? What is the history of this place in relation to Kenya’s state and political economy?

GG: Mathare is one of the first colonial settlements for the people who were evicted from their land by the British settlers. Some [of the displaced] located themselves in Mathare, which was a slum. So Mathare became a place of lower class people, that were being exploited by the colonial economy. After that, it was used as a quarry. Mathare is at the heart of the construction of Kenya’s neocolonial state and economy. It has a major history. In fact, one of the major roads that cuts across Mathare is the Mau Mau Road. This was a home of also Mau Mau freedom fighters [during the struggle for liberation]. So, Mathare is a symbol of the independence struggle. We are building from that history. Mathare also is a place where you will find members from all ethnic communities of Kenya. So, it is a cosmopolitan place, a melting pot of Kenya. It is the place from which we are trying to forge a new Kenya, a new social justice nation.

A view of Mathare

LM: What are the main problems and challenges that people, particularly youth in Mathare and places like Mathare, confront on a daily basis in Kenya?

GG: Poverty is a major problem. Lack of access to clean water. There is no housing and now we are having systematic extrajudicial killing. Because of unemployment, many young people don’t have jobs. So, the state is using tools [like extrajudicial killing] as a cleansing of young people and criminalizing them. So Mathare Social Justice Centre has been documenting cases of extrajudicial killing, because it is widespread, and the state is not accountable.

LM: You are the coordinator of the Mathare Social Justice Centre. What type of work has your organization done to respond to these problems and challenges that you spoke about?

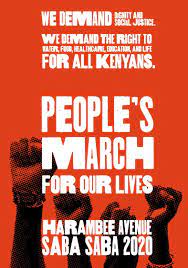

GG: We are not at the level of the state, where we can provide social programmes. But we have done documentation [of human rights abuses] to expose these gross human rights violations and show the limitation of the measures that the state is using to say that it is fighting crime. Also, we have taken a number of cases to court, where we are demanding accountability from the police, or killer cops, as we call them here in Mathare. So, what we have done is to create awareness about the violation of [human rights] that is being done by the state. And also using this to build a grassroots social movement to organize marches, like the Saba Saba March for our Lives, just to demand accountability as we move to call for a democratic state founded on social justice and human rights.

LM: The Covid-19 situation in Kenya has worsened over the last couple of months. In March of this year, Kenya’s president, Uhuru Kenyatta, imposed yet another lockdown in the country. How have the Covid-19 pandemic and these restrictions impacted residents of Mathare and areas like it? How, if at all, has the pandemic exacerbated poverty in these areas?

GG: It is horrible. The pandemic has really exposed [a lot] … and we really have lost a lot of comrades in Mathare. It is difficult, when you put in place a lockdown in places like Mathare, where people live hand-to-mouth, doing causal labour work, going to wash laundry in middle-class areas, going to work in a factory from day to day. So when you put a lockdown in a place where there is no proper housing; there is no clean water; there are no health care institutions, you [leave] people to starve within a very bad condition that has been created by the same government, which never built houses for the people and never created sanitation infrastructure. So, it has been very bad. Many people have suffered. Millions of people have been taken back to poverty. Violence has increased. There is a lot of criminality that has taken root, because a number of people don’t have jobs. For young people also, for almost one year, there was no going to school. There is also the huge problem of young mothers and teenage pregnancy. Increase in rape of young women. There is a lot of social crises that have emerged because of Covid-19 and the unscientific method that was imposed by the Uhuru Kenyatta government. We have been protesting against these and demanding that the government provide us with clean water and building health care institutions within our community. This has not happened.

LM: President Kenyatta has also encouraged Kenyans to work from home, where possible. What does such a directive mean to people living in informal settlements, like Mathare?

GG: That shows a president who is very disconnected from the people he is leading. In Mathare, there is no internet. There is no infrastructure for electricity. So, [working from home] is not possible. And you can’t tell people doing laundry in the city of Nairobi, or hawkers, [or] women who are doing work in the bars [to work from home], because the Kenyan economy is informal. It is this disconnect [between the decisions of government and the lived reality of citizens] that has messed up a lot of people’s lives and this is a major crisis that is continually boiling up every day.

LM: In what ways can we understand the relationship between the struggle against Covid-19 and class struggle more broadly in Kenya?

GG: In terms of people who are affected by Covid-19, the vast majority were poor people. Even the people who had the priority of getting the vaccine were the rich, the middle class. So, you see this is an apartheid of Covid-19. The rich get the vast priority. They can get oxygen. They can get the [hospital] bed. Just the poor people reach to public hospitals. These hospitals are over-occupied. The workers [there] are overstretched. It has been horrid. You go to public hospitals that have been messed up due to neoliberal policies. You see Covid-19 has really affected the majority of the poor people. Our people are dying everywhere.

Kenyan police enforcing Covid curfews

LM: A big part of your political activism, as you mentioned, has focused on the problem of police brutality and extrajudicial killings in Kenya. Can you describe the nature of this problem within the country? How serious is it?

GG: It is extremely serious. One, because the state has failed to provide people with the basics. The state is still anti-democratic. We have an unequal society, where the majority of the people are poor, living in the slums. Some are peasants living in very hard conditions. So, what is happening is that the state is using the police as an instrument of violence to repress people. Because of the weakness of the judiciary and other institutions of the state, the police are using brutality, violence, and forced disappearances, and extrajudicial killing. So that is why we focus on this. It is used to terrify people. And it is used to instil fear in the people, so that they cannot organize against the social problems that the state has imposed on them. Every day we document cases of young people getting killed and then dumped in local public mortuaries. It is the cleansing of poor young people, because the state has no alternative for them.

LM: Extrajudicial killings and police brutality have a long history in Kenya dating back to the colonial period, often with poor youth in the informal settlements being the primary victims of these crimes. Can you talk a little bit about this history?

GG: Kenya is a former British colony. The British colonial state came to oppress people, to grab lands, exploit forced labour and create a very strong police state of violence to coerce people and enforce taxation. This is what was taken over by the independence government of [Jomo] Kenyatta. First of all, there was assassination of the progressive political class, like Pio Gama Pinto. J.M. Kariuki was disappeared, where his body was found in Ngong forest mutilated. So, at that time, police were used to assassinate progressive voices that were demanding social justice. Then after that, you had a Moi administration that was involved in police torture. They built the Nyayo House torture chambers. Those were used to torture intellectuals, professors from the university, workers, who were challenging Moi’s dictatorship. Then you had the Kibaki regime, that’s when they used systematic extrajudicial killing of poor youth from the informal settlements.

We can locate [this state violence] within the history of British colonialism: collective punishment, the killing of freedom fighters, mass incarceration, exhibition killing, shoot-to-kill. Then, for example, we had Kibaki and [Uhuru] Kenyatta, who came also with this policy of shoot-to-kill. It is continual from the colonial government to [the regime of Jomo] Kenyatta, to Moi, up to now.

LM: According to a recent report entitled ‘The Brutal Pandemic” published by the Kenyan organization, Missing Voices, 157 people have been killed or disappeared in 2020 against the backdrop of Covid-19 enforcement measures. In what ways, have the pandemic-related government measures and restrictions altered or intensified the problems of police brutality and extrajudicial killings in the Kenyan context?

GG: Covid-19 and the restrictions imposed by government have intensified police brutality, extortion, and killings. Some of the people in Mathare don’t have proper housing. So, when the government imposed a curfew, people in Mathare didn’t have a house to go to. When they are found outside on the road, they are clobbered [by the police]. We have some cases in Mathare of people who have been shot by police [in such situations] and they died, because [the police] were imposing the curfew.

LM: In May 2020, the murder of George Floyd sparked a wave of protest in the United States and beyond against racial injustice and police brutality. Your organization, the Mathare Social Justice Centre, responded by organizing an event in memory of George Floyd. What type of relationship exists between your struggle against police brutality in the informal settlements of Kenya and the broader Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement?

GG: Our struggles are connected. The black youth everywhere in the United States, they really have faced the same police brutality, criminalization, and mass imprisonment [that we have]. The same poverty, because you are poor as a black. The same thing is happening in Kenya here that you are being imprisoned, criminalized, because you are poor. What happens in Mathare doesn’t happen in the rich areas. So, it is also a class question. The policing of the poor people by the state, especially the capitalist state like the United States, and the neocolonial state in Kenya, they share the same tools of oppression of putting poor people down and that’s why we say our struggle with Black Lives Matter and George Floyd are connected. It is the same police brutality. It is the same dehumanization of poor people. It is the same robbing of dignity of the youth and that’s why we organized the protest of the killing of George Floyd [in Kenya], because our struggles are connected. The struggle against police brutality is all over, whether it is Nigeria, Nairobi, or Minneapolis, where George Floyd was killed.

A man sits under graffiti depicting African-American man George Floyd, who died in Minneapolis police custody, at the Kibera slum of Nairobi, Kenya, June 4, 2020. Credit: REUTERS/Baz Ratner TPX IMAGES OF THE DAY

LM: What types of reforms need to be introduced to adequately tackle the problem of police brutality and extrajudicial killings in Kenya? Do you, for example, advocate for the defunding of the Kenyan police?

GG: First of all, what is very important is that we are demanding for the stopping of training of our security agencies by the state of Israel, which has been arming our police and giving them tactics to use against protesters. That’s very critical, because some of these development partners of the Kenyan police are the ones who have given them the tools of oppressing or doing violence to our people. So, we are demanding instead of putting money to the police, [the Kenyan state] should be putting money to social programmes that mitigate poverty, violence, crime and drugs within the poor communities.

LM: Next year, Kenya will have a presidential election. Is there any political leader or party, which you believe offers a genuine alternative from the political status quo in the country, that you feel you will be able to support?

GG: There is the Communist Party of Kenya that is now registered, that used to be the Social Democratic Party. We have campaigned with them against police brutality. We have Ukweli Party, that is led by Boniface Mwangi. We have a number of political parties and a number of middle-class [political] formations that are coming together as a united front. [For example,] the Makueni Governor, Professor Kivutha Kibwana. We have worked together for some time. If he runs as a presidential candidate, for sure, I will give him my vote, because he is an ally and he has also been fighting against the political class. He has done very well in his county [in] providing for the cooperative society and health care institutions for the poor people. The social justice movement will participate in these bourgeois elections. Not to win, but to offer voices on a social justice vision. At the end, it will be a protracted struggle for a long time.

LM: Last question, Gacheke. In mid-May of 2021, five high court Kenyan judges declared the Building Bridges Initiative (BBI), a government-supported plan to make fundamental changes to the country’s constitution, “irregular, illegal, and unconstitutional”. What is your opinion of BBI? Do you think it would improve Kenya’s electoral democracy?

GG: No. I was on the frontline of opposing that BBI, because it was being used by big ethnic leaders of different ethnic communities so that they can share the spoils of the constitutional structure that they were trying to split. It was not in the interest of the people. It was not designed to benefit the poor. It was not anchored on any kind of social justice programme. It was just something that Odinga and Kenyatta came up with to try to sanitize their failure of resolving the historical programme of electoral injustice. Instead of resolving the problem of the land question, they wanted to have compromise between themselves, on how they can share power, and hoodwink Kenyans. So, I opposed it.

New Email List of LinkBio Users. Sell your products or services directly with cold email marketing to Instagram users that uses LinkBio in their profiles Download it from here“>”>”>