Is Tunisia’s democracy slipping away?

President Saied has been running the country unilaterally for almost a year. The July referendum will further strengthen his rule without resistance.

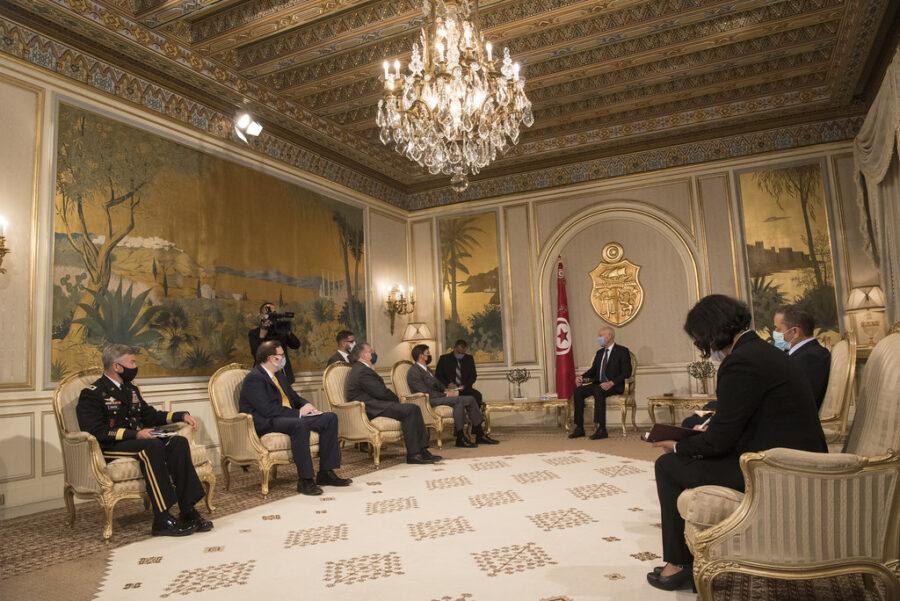

Tunisia’s President Kais Saied meeting with then US Defense Secretary Mark Esper at Carthage Palace, Tunisia, in September 2020. Credit: DoD/Lisa Ferdinando.

Those sincerely committed to the protection of global democratic norms must avoid the strategic error of ignoring the collapse of nascent democracies such as Tunisia. The birthplace of the Arab Spring, what happens there matters not just to the country itself, but to North Africa, the Middle East, and beyond.

Since the 2011 uprisings, Tunisia has largely been a beacon of hope for democratic aspirants across the region. While its neighbours have seen the reassertion of authoritarian rule or sunk into domestic turmoil, the smallest of the North African nations has witnessed fair elections, a free press, and the establishment of the Arab world’s most progressive constitution.

All this democratic progress, however, has been on a knife’s edge for the last year. On 25 July 2021, President Kais Saied declared a state of emergency following popular protests against the economic recession and the government’s poor handling of the Covid-19 pandemic. Saied claimed his move sought to rectify Tunisia’s political path and a dysfunctional parliament. He proceeded to shut down all political life and crippled post-uprising institutions. He sacked the Prime Minister, froze and then dissolved parliament, shut down the Supreme Judicial Council, and seized control of the election commission.

Saied’s intervention initially enjoyed overwhelming support from a citizenry that had grown frustrated at the government. According to a July 2021 poll, 87% of people welcomed his measures. However, this mood has since changed. By January 2022, that support had nearly halved.

For almost a year now, President Saied has been ruling Tunisia unilaterally with no checks and balances on his power. Though he claims to uphold respect for democracy, human rights, and freedoms, there is no evidence that this is anything but lip service and an attempt to buy time while he consolidates his power grab. The reality is that there has been increasing legal prosecution of political opponents, whom Saied has labelled as corrupt or treasonous. The free media is being stifled, and military courts are being used to quell dissent.

Tunisia’s political strife has also exacerbated the crisis in the economy, which has been weakened further by the impact of the war in Ukraine on wheat supplies and commodity prices. In March, Fitch downgraded Tunisia’s sovereign debt to junk status. Some economists predict that without the $4 billion IMF loan Tunisia is eying, the nation could face a financial meltdown.

Saied is now proceeding with a referendum on a new constitution to be held on 25 July. He is pursuing this move despite strong pushback from the political opposition, leading academics, and the one-million-member-strong UGTT trade union, which initially backed the initiative. These groups have all refused to participate in a national dialogue to draft the new constitution. The UGTT has also called for a national public strike in June after the government refused to raise wages, a move by the state aimed at helping catalyse the IMF deal.

Trust between the presidency and opposition parties, national organisations and civil society has plummeted, exemplified by back-and-forth accusations of treason between opposing sides. Yet no substantive reforms, especially economic reforms, are possible in Tunisia without effective, inclusive, and continuous dialogue between the nation’s various political actors.

Protecting Tunisian democracy

It is imperative that national democratic forces in Tunisia continue to pressure President Saied to reinstate a system of checks and balances and ensure the participation of all main political factions in any national dialogue. They must condemn human rights violations and condition any type of cooperation on political accountability and the reinstatement of democratic standards, including in the state’s deals around military and economic aid and the proposed IMF loan.

Western democracies have a role to play too. They cannot watch passively as Tunisians are condemned to a life of dictatorship and all democratic stirrings in the Arab world are destroyed. The uprising that toppled Zine El Abidine Ben Ali in 2011 was, and remains, a chance for Tunisia and its neighbours to democratise a region entrenched in authoritarianism. The West must make good on its promise to stand up everywhere for the democratic values it aims to promote.

Tunisia lacks true democratic leaders. Tunisian civil society is also isolated and short of experience and awareness of democratic principles. Donor organisations therefore have a responsibility to support civil society by focusing on projects that will help advance fundamental (non-superficial) democratic values and norms. This will empower Tunisia’s civil society to build the vision and mechanisms to guide a new generation of democratic believers.

The survival of Tunisia’s democracy is key to any hopes for democratic governance in the Arab world. The outcome of its political crisis could reverberate across the region and beyond for a long time.