A Trojan Horse in Carthage

How did Kais Saied, a retired law professor, become a tyrant? Answer: with the support of the pro-democracy movement he now oppresses.

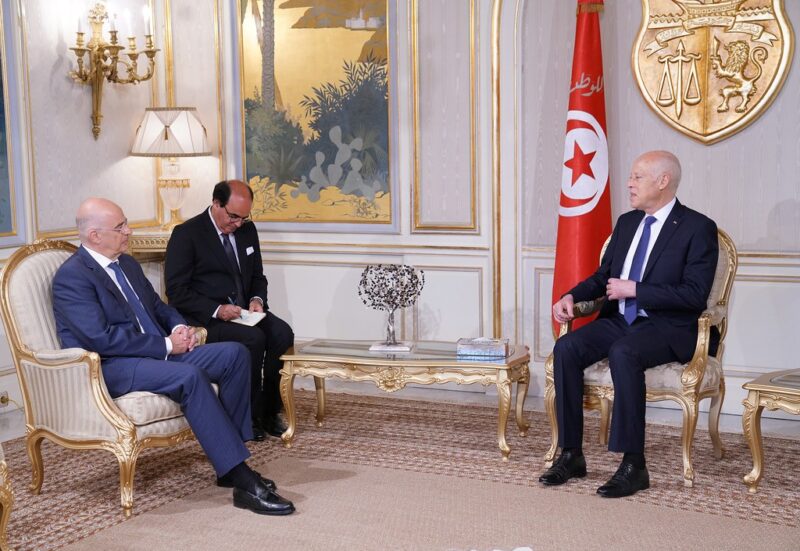

President Kais Saied (right) meeting with the Greek foreign minister. Credit: Υπουργείο Εξωτερικών.

Everyone knows the legend of the Trojan Horse: after years trying to storm the city of Troy, the Greeks pretended to withdraw their troops and gifted a beautiful wooden horse to the Trojans, claiming it was a step towards peace. Greek soldiers, hiding inside the horse were smuggled into the walled city. Once in, they opened the gates letting their army in to invade and sack the city. I see a chilling parallel with what has happened to Tunisian democracy.

After the Tunisian people vanquished authoritarianism during the 2011 revolution, the years that followed were marked by repeated attempts by counter-revolutionary forces to march back these reforms. These forces eventually succeeded.

Elected in 2019, President Kais Saied rapidly became the arm that would demolish the country’s prospects for greater freedom. He presented himself as someone who listened to and cared about his people, only to serve the interests of the darkest reactionary forces, determined to stop the country from moving forward.

Saied does not have any real legal or popular legitimacy in Tunisia. This was proved in the recent elections where the voter turnout for the Tunisia’s legislative elections did not exceed 8.8%, the weakest participation rate in Tunisia’s history. What took place was, in actuality, a referendum on the person of Kais Saied, and on his project and constitution. It is crystal clear to the world: he is just a coup leader usurping power and, at this point, lacking the courage to submit his resignation.

Tunisia was a regional success story that fell apart within months. Observers fail to understand that it was a combination of forces that caused a devastating blow to years of struggles and advancements. On 25 July, 2021, President Saied dismissed the parliament, sacked his prime minister, amended the constitution, and got rid of almost every vestige of democracy. Believing that for the coup to fail, Saied must be the sole one to fall is a deep misunderstanding of the country’s contemporary political turmoil.

In Tunisia, as in all societies, there are forces that pull back and forces that push forward. In 2021, as Saied concentrated tremendous power in himself and started ruling by presidential decree, not a single so-called pro-democracy organisation inside the country protested.

In a climate of economic anxiety and tension, the masquerade began.

Saied arrived as a saviour, denouncing corruption, and posing as the remedy to chaos while promising people a utopian future. He spoke of revolution, and of real democracy, things in which he had actually never partaken. Eventually, the pandemic, the restrictions that came with it, and the financial fallouts, accelerated the democratic ambush as a large segment of Tunisians sought to exit from the country’s economic woes by whichever means necessary.

There are so many enablers of this dictatorial turn that they are almost impossible to list.

I am thinking of Tunisian human rights organisations and news outlets such as Nessma and al Tunisi networks. The Tunisian General Workers’ Union; the National Union of Tunisian Journalists; the League for the Defense of Democratic Women, and all those others that issued statements of support as Saied announced the state of emergency and the dissolution of parliament. The media, owned by groups loyal to the regime of former dictator Zine el Abidine Ben Ali, contributed to the distortions of the revolution and democracy in the minds of the people. They fuelled culture wars over religion, secularism, modernity, and equality in inheritance, diverting the debate away from the pressing issues of social justice, distribution of wealth, and unemployment.

Since his draconian moves in 2021, Saied has failed at all levels: under him, Tunisia has experienced the collapse of the dinar against the euro, worsening unemployment, food shortages, abysmal turnout at the referendum, a boycott by the majority of parties to the legislative elections, low turnout for candidacy in these elections (there are districts with zero candidates and there are districts with only one candidate). The public’s lack of interest in these elections is, to say the least, telling.

When the president tried dozens of civilians before a military court, when the politician Noureddine Bhiri disappeared after an arrest and came out two months later in December 2021 carrying serious injuries, these same organisations again did not utter a word. While only 27% of the electorate participated in the referendum on the new constitution, the electoral commission in charge of it – quite naturally, appointed by the president – inflated this figure to 30.5%, and still called it “successful” and “historic”.

The “Citizens against the Coup” movement went on a long and violent hunger strike in the Covid era to condemn the coup; no official human rights organisation issued any statement supporting them.

These forces are the makers of the Carthage’s Trojan Horse and, along with the army and security forces, are its enthusiastic cheerleaders.

Gulf States such as the United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia brazenly supported the destruction of democracy in Tunisia fearing that, if successful, it would set a dangerous precedent for citizens in their own autocratic states. France too has backed Saied’s moves, clearly happy that Tunisia’s Islamist Ennahda movement (previously the biggest bloc in the parliament that Saied dissolved) was vanquished.

The world needs to stop considering every Islamic party as necessarily extremist and anti-democratic. The Ennahda movement has been involved in Tunisia’s political process since 2011 and has always been the biggest or the second-biggest party in parliament. It has not engaged in any violence. It is the most important party and has staged demonstrations for one-and-a-half years agitating for the restoration of parliament and the 2014 constitution. Ennahda continues to resist the authoritarianism of Saied. Its contribution to Tunisia’s democratic journey cannot be denied.

Aside from the exaggerated fear of Tunisia’s Islamists, the world needs to know that there are other pro-democracy liberal and secular local Tunisian actors that deserve to be emboldened, including all the local organisations and movements that have been oppressed by Saied and received insufficient support domestically and internationally by those that claim to uphold democratic values.

The international community must put more pressure on Saied to restore the 2014 constitution and organise legislative and presidential elections. This way, the elected parliament will amend the political system and establish the Constitutional Court and the rest of the necessary institutions to ensure the stability of democracy.

I don’t see all the setbacks Tunisia is experiencing as a final chapter in our transition to a more egalitarian society. Believing that the Arab World cannot have a sustainable democratic system is wrong-headed orientalism. The road was complicated in many places in the world. But we will continue to fight for democracy in Tunisia, as a pioneering example for the Arab region, and we need the international community to support us.