“Mainstream history was written by the coloniser…it’s time we wrote ours”

An interview with Leila Aboulela whose latest novel returns to Khartoum’s 1884 siege to make a case for a different construction of history.

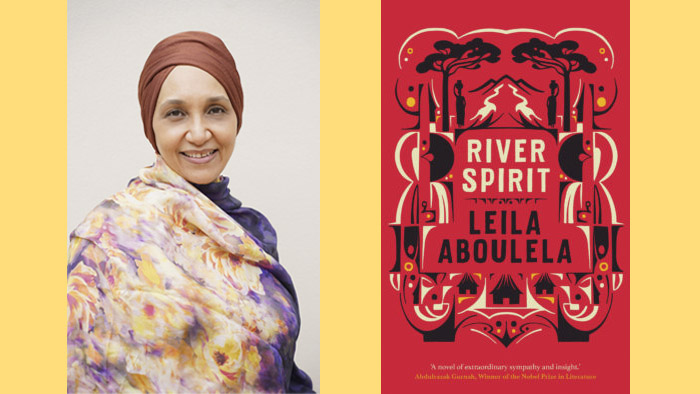

Leila Aboulela (Courtesy: Victoria Gilder PR)

AFRICAN ARGUMENTS: First, warm congratulations on yet another literary milestone. We would love to know how you came to write this book. Could you tell us about its genesis?

LEILA ABOULELA: I grew up in Khartoum. Our house was about 4km away from the palace on the Blue Nile where, in 1884, an embattled General Charles Gordon used to stand on the roof, looking out with his telescope, desperate for the arrival of the British relief expedition. Khartoum was under siege by the armies of the Mahdi and that thrilling story with its tragic ending is something that has always enthralled me. Knowing the location well and studying the history in school and university, made it a familiar backdrop against which I could set my novel. The very initial idea for River Spirit was of a young man from Edinburgh who becomes fascinated by the vernacular architecture of colonial Sudan. He paints the Nile and starts to dress like a native. When he sketches the wife of a tribal chief and the drawing is discovered, his career and safety are in jeopardy. I ended up deviating quite far from this original idea. As I was writing, the woman in the drawing/ painting took centre stage, and the artist no longer became the main character.

AA: The book centres on Akuany, an orphaned girl who is sold into slavery. Where did your inspiration for her character come from?

LA: In the Sudan Archives at Durham university, I found a bill of sale for a woman called Zamzam. I was shocked by this discovery. I knew that slavery existed in nineteenth century Sudan, but to hold in my hand a bill of sale, with an actual monetary figure and the names of the people involved, was quite startling. I also found a petition detailing the case of an enslaved woman who had escaped with a stolen item of clothing from her mistress. She had gone back to her former master, and it was against him that the petition was raised. I found this situation intriguing and complex enough for me to want to fill in the gaps with fiction. I started researching East African slavery, the extent of it, how it differed from the transatlantic West Coast slavery and how nineteenth century Sudan was a gateway to the lucrative markets of Cairo and Istanbul.

AA: Akuany isn’t the book’s only female voice – other characters include Fatimah, Yaseen’s mother, and his wife, Salha. It’s refreshing to have so many female voices on a period that we usually only hear through the voices of men. Could you talk a little about this?

LA: Unfortunately, women are merely footnotes in the historical records. I had to dig and pick up threads here and there. Certainly, I never found a first-person account from a woman’s perspective. Throughout the Mahdist wars, women accompanied the army. They cooked, nursed and set up market stalls every step of the way. They also played a part in espionage, gathering data and passing it on – this inspired the role played by Yaseen’s mother in the novel. I was also excited to discover that the Mahdi had sent a woman ambassador to the Khartoum palace. I also used that in the novel.

AA: As popular interest in the historical novel in Africa grows, what are your thoughts on its future in African fiction?

LA: Mainstream history has been written by the coloniser. This is their truth. It is time for us to tell ours. When Africans write history, we are not necessarily saying something about the world today. Much of the motivation comes from wanting to tell our side of the story. I am more excited by African historical novels than by any other genre. At the moment, Africa’s encounter with Europe is the focus of much historical fiction. Perhaps in the future, writers will move away from this and delve into the even deeper past before European colonialism. There is a rich, fascinating history that needs to be told.

AA: Could you please share your experience of researching and writing this novel? While a number of the central characters were actual historical figures, were the other major characters purely invented, are they composites of individuals you encountered during your research, or are they stand-in figures perhaps for individuals you did not want to name?

LA: None are stand-in individuals. The actual historical figures were the Mahdi, Gordon, Sheikh Amin Al-Darir and Rabiha. Much has been written about the Mahdi and even more about Gordon and there were his journals too. So apart from conjuring up Gordon’s voice, there was a large amount of material to work with – and that posed a challenge too because I had to be selective. On the contrary, there was very little on Al-Darir, head of the Khartoum ulema, so I depended on my imagination. Rabiha appears in the historical records as a footnote – the woman who overheard a conversation as she was herding her goats and then ran through the night to warn the revolutionaries about the government’s intended attack. She is mentioned time and again in every record but with little detail. I enjoyed fleshing her out and elevating her position through my imagination.

AA: Could you tell us more about the concept of the ‘Mahdi’ in Islam?

LA: The Mahdi is not mentioned in the Qur’an. He is, though, described in great detail in many of the sayings of the Prophet Muhammad صلى الله عليه وسلم, the Hadith. He is described as the Expected Redeemer, the Rightly Guided One, who would, close to the end of Time, bring justice and prosperity after years of earthquakes, tyranny and oppression. His name would be Muhammed Abdullah, he would rule for seven or eight prosperous years and during these years many of the imminent signs that herald the end of the world will take place. Throughout the history of Islam, around thirty men claimed to be the Expected Mahdi.

AA: You speak of having grown up 4km from Gordon’s Palace. Are there any other elements of your family’s history in the novel?

LA: My great grandfather was an immigrant from the south of Egypt, and he was an employee in the colonial government. He was staunchly opposed to the Mahdi in every possible way. When the Mahdi and his army entered Omdurman, my great grandfather dug a pit in his yard and hid his five daughters there because he was afraid they would be raped. I used the idea of the pit in the novel but to hide a man rather than young girls!

AA: Given your reliance on the colonial archive, do you believe it is important to widen access especially to Western archives for writers who do not have access to records of their own history? We ask this in the light of the current artefacts restitution campaign. While its target is looted African artefacts, the bulk of the colonial documentary archive was carted off to imperial capitals at the end of the colonial era and remains largely inaccessible to Africans on the continent. Is there a need for a similar restitutive campaign targeting the colonial archive?

LA: Because I am bilingual, I did not need to rely solely on the archives found in Britain. Half of my research was dependent on Arabic records. Even though some of these primary sources had been translated into English and I read English faster, I read them in the original Arabic. They are brilliant because they expose ordinary people’s day to day lives during these wars. Through them I was able to learn about the texture of life at the time, how people ate, travelled, communicated, their expectations and anxieties. In answer to your question, I believe it is important to widen access and a restitutive campaign is justified. I would also stress the issue of records written in mother tongues and translations because it is within these local languages that the primary African perspective resides. It is shocking for example that one of my most valued primary sources, The Memoirs of Babiker Badri (born in 1861), written in Arabic and widely published in Sudan, is out of print in its English translation. And even that translation, carried out in the early 1960s can do with some freshening up. This is a vital African text and yet it is not widely accessible due to the issue of translation. I am sure there are other texts too, written in African languages, that need to be translated and published.

AA: Finally, we are eager to hear more about your research into slavery in the old Ottoman Empire that tyrannised much of East Africa and the Horn. What is its enduring legacy in the region, its hinterlands and diasporas?

LA: To my surprise, I did not find abundant resources on East Coast Slavery. It is definitely an area that needs to be further researched. Ironically after decades of active engagement in the trans-Atlantic slavery, Britain launched a passionate attack on the Ottoman/Arab/Egyptian slave trade. Suppressing it became a reason for British expansion and the subsequent colonisation of Sudan. As a result, much that was written about the Ottoman slave trade is laden with a righteous European indignation that was intent on justifying the need for colonial expansion in order to suppress the brutal East Coast slave trade. When people think of slavery, they are likely to think of the long Atlantic passage and the plantation culture accompanied by deep systematic racism. The East Coast slave experience was different. Capitalism was not the driving force of the Arabs and Ottomans. Instead, they mostly enslaved men for military service and women for domestic labour. You ask about the legacy. When I read about the Sudanese child soldiers recruited by Saudi Arabia for their war in Yemen, and the Ethiopian maids abused in Lebanon, my blood runs cold.

River Spirit by Leila Aboulela is published on 7 March by Saqi Books.

Without a doubt it is necessary to rewrite our own narratives. It is like the old saying “As long as the hunting stories are only told by the hunter, the lion will never have his place to speak”, so it is important that we can write/produce our own narratives.

I might take issue with the issue of having African history written by Africans. In theory it’s a good concept, but the reality is challenging. Prior to the introduction of literacy , most history was oral. I’m a member of a number of Southern African history groups, and there is enormous disagreement on that oral history, as it has become tainted down the years by prejudice, both inter-racial and inter-tribal. Those African writers who have written on aspects of Southern African history reference white-written history, those that are factual. not political.

But there ARE sources which one might call ‘indigenous’ ( eg interviews written in the late 1800s/early 1900s with people who were alive, or whose parents were alive, in the pre-colonial era) And this is where i might disagree again. They ARE accessible. Massive online resources , and in libraries and archives. But Facebook history rules and people are not prepared to make an effort to use those resources. It’s not fair to say archives were removed to imperial capitals. The British, great lovers of bureaucracy, left copies of records which are now in local archives. Not all for sure, but I can tell you that there’s a massive archive of material waiting for someone to read (someone other than me!), but sadly, it’s easier to dip into Facebook, and its ‘truth by repetition’