Nigeria’s Happy City is on the brink of being swallowed by the sea

As the community await international funding and national action, the once reputed coastal town is disappearing in rising ocean surges.

Akingboye Thompson points to remains left by the ravaging sea, which continues to rise along the coast of Nigeria. Credit: Abiodun Jamiu.

On a spring morning in April 2006, the residents of Ayetoro roared as the Ayetoro Boys took on Flamingo in the final of an inter-communal football competition. The evenly matched contest was heading to penalties when the Ayetoro Boys took one last throw of the dice by subbing on the then just 15-year-old Akingboye Thompson. The gamble paid off. Thompson scored a stunning header that won his team the trophy. He was carried shoulder high amidst cheers from the whole town.

“The day was my fondest of this community,” reminisces Thompson, now 32. “Every single moment was spectacular.” As he wanders the edge of this coastal town, he recalls a childhood spent playing on the seashore and watching fishermen go about their daily business. These memories are now bittersweet. Over the years, rising sea surges have gradually claimed most of Ayetoro – including the once parched football pitch.

“If you come in the next two weeks… where we stand right now might have been submerged,” says a downcast Thompson. “It’s so absurd and pathetic.”

Founded in 1947 by Apostolic missionaries, the town of Ayetoro in Ondo state, Southwest Nigeria, was once reputed for its buzzing communal life and sophisticated fishing, carpentry, shoemaking, textiles, and more. Situated on the Atlantic Ocean, tourists appreciated its beauty and serenity. The town became known as Nigeria’s “Happy City”.

Over the last 20 years, however, rising sea levels and more intense storm surges have battered Ayetoro. Recurrent floods have damaged hundreds of buildings – including homes, schools, and even cemeteries – and swept away over 50% of the town, which is now below sea level. The population, some of whom lived there for countless generations, has depleted from around 30,000 people in 2006 to just 5,000 today.

Those that remain are on borrowed time. Omogoriola Ajinde, 45, awoke to the angry roar of the ocean as it swept through houses on the night of 19 April 2023. He escaped with his wife and children, but little else. “I couldn’t even take a pin out of my house,” he says. “Everything I worked for over almost 30 years was gone in a flash.”

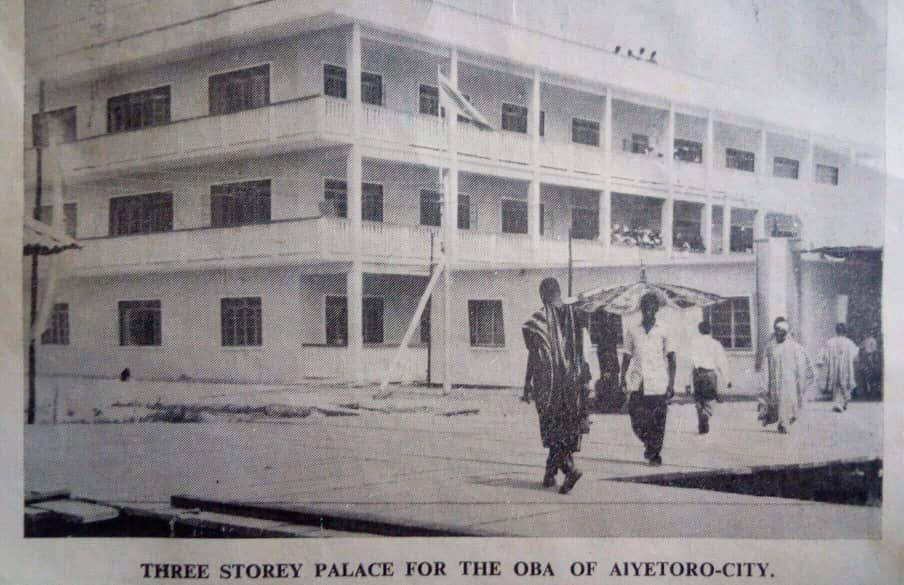

An image of Ayetoro in its heyday, before the rising sea surges.

Stretching from the fringe of the Sahara to the Gulf of Guinea, Nigeria is one of the most vulnerable countries in the world to climate change. Desert is encroaching its northern pastures. Erratic rainfall and drought threaten its farmlands. And the Atlantic Ocean continues to consume areas along its 850km-long coastline. According to a World Bank report, a 0.5-meter rise in sea level could force 27-53 million Nigerians along the shore to relocate by the end of the century.

In the case of Ayetoro, some people also blame nearby oil exploration for making the town more vulnerable. “The process of drilling and extraction weakens the land,” says Mayokun Iyaomolere, an expert on environmental control and disaster management. “In a low-lying coastal area like Ayetoro, it makes the community more susceptible to an ocean that is already rising”. Oil firms have denied responsibility.

In response to the sea surges, the community in Ayetoro has long attempted to protect itself. In 2009, for instance, leaders from the town visited The Netherlands to learn how the flat low-lying European country has managed to protect and reclaim its land from the ocean. They presented their findings to authorities in Nigeria, but nothing came of it.

The interventions of the Niger Delta Development Commission met a similar fate. In 2004, the government agency instituted the Ayetoro Shore Protection Project, promising to build a sea embankment to shield the town from tidal waves. Marred by corruption, the project was eventually abandoned.

More recently, in 2021, Nigeria passed the Climate Change Act to provide a framework to mainstream climate actions. Iyaomolere suggests the policy is good on paper but says it has not improved crisis preparedness, citing the devastating 2022 floods that displaced 1.4 million people and killed over 600 across 33 of Nigeria’s 36 states. “It was obvious there was no measure in place to mitigate climate disasters,” he says. “In places like Ayetoro and other coastal communities, that is what they have been facing for more than a decade.”

Baliqees Salaudeen, a climate justice activist, echoes these frustrations. “That we have communities in the country still experiencing climate-related disasters like flooding and sea incursions every year say so much about our climate plans and the need for a more realistic and sustainable approach,” she says.

Some remaining buildings, now at risk, in Ayetoro. Credit: Abiodun Jamiu.

While Ayetoro today is a ghost of its former self, experts like suggest Iyaomolere that what remains of the town can still be protected. A coastal embankment could stop the ocean from advancing further, while an early warning system can help safeguard the remaining population. Where the consequences of rising sea levels are unavoidable, support can be provided to help residents relocate.

A key impediment to all these actions, however, is funding. Some estimates suggest that the world’s poorest countries will need $300 billion per year to compensate for “loss and damage” alone (i.e. negative effects of climate change that cannot be mitigated or avoided). Other studies put the figure needed at almost double.

Last year, developed economies – which are responsible for nearly 80% of historic greenhouse gas emissions – relented to years of pressure and agreed to set up a loss and damage fund. In theory, this will provide financial assistance to developing countries hit by climate disasters, but questions remain over its implementation and arrangements. Meanwhile, the Global South is still waiting for developed countries to fulfil a previous promise to mobilise $100 billion per year in climate finance by 2020.

Don’t miss a thing. Sign up to the free African Arguments weekly newsletter.

“Delay is dangerous,” says Ajinde, who escaped the sea surge in Ayetoro this April. “If nothing is done within the shortest possible time, the community would be wiped away from the surface of this earth.”

Indeed, as the wait for international funding and national efforts goes on, more and more of Nigeria’s Happy City crumbles to the sea. Years of inaction down the line, the once strong community is running out of options. “If there is anything we can do on our own to restore Ayetoro, the world can trust us on it, but this is now beyond us,” says Emmanuel Aralu, Secretary of the Ayetoro Youth Congress. “The least we can do anytime the sea comes is for the whole community to rally around the victims and ensure that they are relocated to a safer place.”

This is where the town’s leadership has focused its attention recently, though this is no permanent solution either. Ajoke Maria, 35, has moved upland three times as the ocean has continued to sweep forwards.

“The sea swallowed the entire house,” she says of the surge that destroyed her home in Ayetoro. “We couldn’t even retrieve anything; they’re now below the feet of the sea. I have to start from the beginning.”

Remains of buildings in Ayetoro, Nigeria, that have disappeared as the sea continues to rise. Credit: Abiodun Jamiu.

move people inland

that the solution