Swaziland in Crisis?

There is a sense that the little nation of Swaziland is in crisis yet again, but this time it is one that won’t go away. There are three elements: political; economic and wellbeing.

There is a sense that the little nation of Swaziland is in crisis yet again, but this time it is one that won’t go away. There are three elements: political; economic and wellbeing.

The Swazis have lived in present day Swaziland since the 18th century, giving the nation a sense of identity and continuity. It was a British Protectorate. King Sobhuza, crowned in 1921, reigned over Swaziland up to his death in 1982, leading the nation to independence in 1968. Following the first post-independence election in 1973, the King dissolved parliament, repealed the constitution and declared himself absolute ruler. His son Mswati III was crowned in 1986. He is an absolute monarch who sealed his power in the “˜Constitution’ of 2006. Opposition political parties are banned; political freedoms curtailed. This is at odds with the trends in the region. The pressure for political reform seems to go unheeded, however the economy and welfare of the nation is under such pressure there may well be change.

The economic crisis is due to falling revenue and low growth. Receipts from the Southern African Customs Union (SACU) which comprises Botswana, Lesotho, Namibia, South Africa, and Swaziland, historically constituted more than 60% of the nation’s revenue. SACU revenue, from regional import and excise duties, is divided between member states. This has been decreasing due to lower tariffs (a global trend), the recession, and fewer imports. The fall in revenue has lead to government being near bankruptcy – this was seen in a request for a R1.2 billion loan from South Africa in late June 2011.

Lower growth is due to a lack of investment and static agricultural output. Swaziland’s uncertain political scene makes it unattractive for foreign investors. The Swazi currency is pegged to the South African rand which is has been very strong for some years, and the Swazi financial crisis has lead to discussions about delinking the currencies.

Most of the Swazi population (about 75%) live in rural areas and depend on subsistence farming. Land is owned by the “˜nation’ and allocated by the chiefs, meaning there is little incentive to invest, leading to low agricultural productivity.

Probably the greatest threat to Swaziland’s wellbeing and hence economic growth and societal integrity is the HIV epidemic. Swaziland has the highest HIV prevalence rate (26%) and also the lowest life expectancy (32 years) in the world. World Health Organisation data estimates about 2% of the Swazi population dies from AIDS every year. In 2009 Prime Minister Themba Dlamini declared a humanitarian crisis due to the combined effect of drought, land degradation, increased poverty, and HIV/AIDS[i].

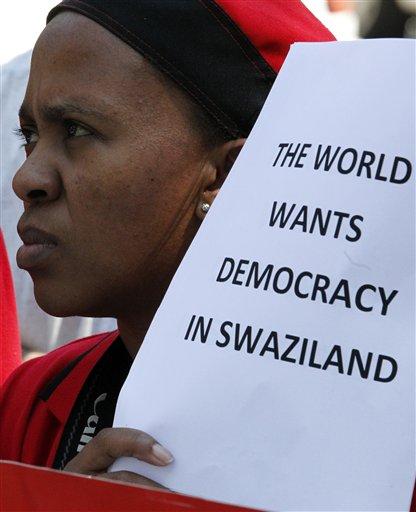

Public discontent with King Mswati’s absolute rule and the country’s economic decline in the country was first evident in 2010, when several hundred people took part in pro-democracy marches in Mbabane. This intensified in early 2011, with protest action being initiated through a Facebook campaign in March 2011. Activists, many inspired by the recent uprisings in the Middle East, marched against a planned public sector pay freeze. These protests were much larger than previously. The leader of the banned opposition People’s United Democratic Movement (Pudemo), Mario Masuku, is quoted as saying that “Swaziland cannot remain an island of dictatorship in the sea of democracy… Royalty has squandered the economy… We want a government by the people,”[ii]. The protesters handed over a petition to Prime Minister Barnabas Dlamini, demanding that he and the cabinet resign.

In April 2011, further protest to mark the 38th anniversary of the banning of political parties was planned by students, unions and political parties in Mbabane, Manzini and Nhlangano. This action was declared illegal, and the government threatened to take action against protesters. Security was tightened, cars at the Swaziland/South Africa border were searched, and activists were arrested and detained. Journalists covering the protest action were harassed and their equipment confiscated. Protests have continued throughout May and June, culminating in a march on 22 June to demand an end to Mswati’s reign.

The country faces a ticking clock and it is unclear that it will summon the leadership needed to get out of the multilayered crises.