Frantz Fanon’s Afterlife: On the 50th Anniversary of His Death – By Michael Keating

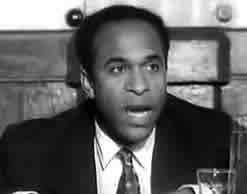

Frantz Fanon (1925-1961) was born in Martinique. He joined the Free French Army and fought in Europe during World War II. After the war he studied psychiatry and philosophy in France until being assigned to a psychiatric hospital in Algeria at the time of the Algerian anti-colonial war against France. It was at that point that Fanon rejected his ties with France and emerged as a spokesperson for the Algerian cause and a strategist for the struggle. Since his death he has been embraced by revolutionaries and social activists around the world. He died on December 6, 1951 at a hospital in Maryland from leukemia. He was 35 at the time. His two most popular works are “Black Skin, White Masks (1952) and “The Wretched of the Earth” (1961)

Two simple questions animated the writings of Frantz Fanon: what are the responsibilities of a black man, and what are the responsibilities of a revolutionary? At first glance the two issues seem inextricably linked. But when we actually delve into the words he spoke, we quickly see that these were questions that have no essential relationship to one another. In fact, for Fanon, it would be a form of Sartrean-style bad faith to conflate them.

For Fanon, the fact of being black in no way tied him to the “˜burden’ of being black. “I am not the Slave of the Slavery that dehumanized my ancestors,” he wrote at the conclusion of his classic 1952 study of Black identity, Black Skin, White Masks. According to Fanon, in coming to terms with himself the black man has a number of choices. He can point to the terrible past and locate himself in the stream of resentment that flows from it, or he can look at the present and the future and declare himself free not only of the “˜Negro identity’ that the white man is looking to lay upon him, but also from the “˜Negro mission’ which some in the black community see as a legacy of birth.

Fanon would have none of either choice.

Existence precedes essence, in the existential vernacular. Fanon believed that the notion of a “black world” sitting beside a white one was fraudulent, and that he had the right to the whole history of the world as his own, rather than a truncated “African” version meant simply for Africans or their descendants. He believed that the legacy of the Enlightenment and the philosophy of the Greeks and the meditations of the great Chinese moralists were all for him, no matter how much the European man or the Asian man would try to claim these things for himself alone.

In the matter of modern European culture, however, he was unequivocal. For the liberated African, this Europe was no model. In the work he is most famous for, The Wretched of the Earth, he writes “if we wish to reply to the expectations of the people of Europe, it is no good sending them back a reflection, even an ideal reflection, of their society and their thought…we must turn over a new leaf, we must work out new concepts, and try to set afoot a new man.” Further on he writes: “Europe now lives at such a mad, reckless pace that she is running headlong into the abyss; we would do well to keep away from it.”

In his famous, almost reverential, preface to the 1961 edition of The Wretched of the Earth, the French philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre sarcastically asks: “What? They are able to talk by themselves?” Sartre saw in Fanon the embodiment of a new type of “˜native’: one who rejected the need for accommodation, one who embraced violence as a means of self-creation. For Sartre, the oppressed had no choice but to burn down the colonial house.

These days, in the Age of Terror, sentiments of this kind would likely land their speaker in a cell at Guantanamo. Put these words into the mouth of an Egyptian or a Pakistani, and he or she would be branded as a fanatic.

But that’s the problem right there, isn’t it? The War on Terror is an unsubtle way of reframing the significance of violence in favour of the most powerful. Globalization has brought the Casbah to the high street. The destruction of two office buildings in New York City is used as justification for the destruction of an entire country because the leadership of that country dared to poke a stick in the eye of the Hegemon. Violence is never legitimate unless it is exercised by those possessing the greatest reserves of it.

During the period of decolonization, it was revolutionary Marxism that fuelled the analysis and the actions of Fanon’s generation. These days, while it is hard to imagine the hard- headed Fanon embracing radical Islam in any manner, he would have recognized the rage that sits at the heart of it. One of the great losses in the fall of the Soviet Union is that the Marxist critique, the very language of Marxism, became somehow delegitimized. The insightful baby was tossed out with the foul bathwater of Soviet despoliation. Although Fanon rarely descended into Marxist cant, the spectre of existential Marxism animates all his writings. Revolutionary existence precedes liberated essence.

Nowadays, instead of having the powerful engine of Marxist dialectics to analyze their concrete situations, the contemporary African has been left with either the rantings of medievalists, the puffery of pseudo-nationalists or the bromides of the development discourse. One can only wonder what Fanon would have made of the humiliating show-jumps which are the Millenium Development Goals. Fanon’s greatest fear for the post-colonial era was that the national bourgeoisie would be co-opted by their own pleasure-seeking and hegemonic instincts. “Now the nationalist bourgeoisies, who in region after region seek to make their own fortune and to set up a national system of exploitation, do their utmost to put obstacles in the path of this Utopia.”

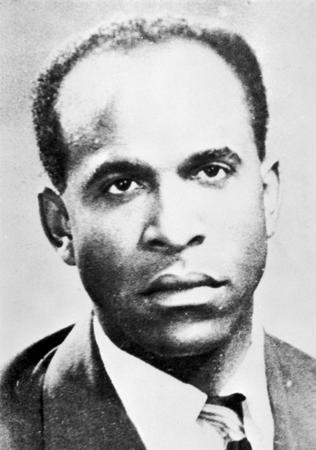

If there is any heir to Fanon in contemporary Afro-discourse, it might be the Ghanaian scholar George Ayittey, who has made a career out of revealing the nakedness of the majority of Africa’s modern presidential emperors. Unlike Fanon, however, Ayittey believes in the basic virtues of free market capitalism, mainly because the first generation of post-colonial rulers made such a bloody mess of their pursuit of an Afro-style socialism. Fanon, who didn’t live to see any of it, may have agreed, although there is damning evidence that the Marxists of his generation, Sartre included, were unable to see much of the ugliness of what they were birthing. Like Che Guevara and Patrice Lumumba, Fanon died just when his torch was burning brightest.

It is up to the new generation of Africans to carry it forward.

Michael Keating is a Lecturer in International Relations at the University of Massachusetts Boston with a special interest in the Mano River countries of West Africa.

He can be reached at: [email protected]

Could you, please, explain a bit more what makes you say this sentence?

“One can only wonder what Fanon would have made of the humiliating show-jumps which are the Millenium Development Goals. “