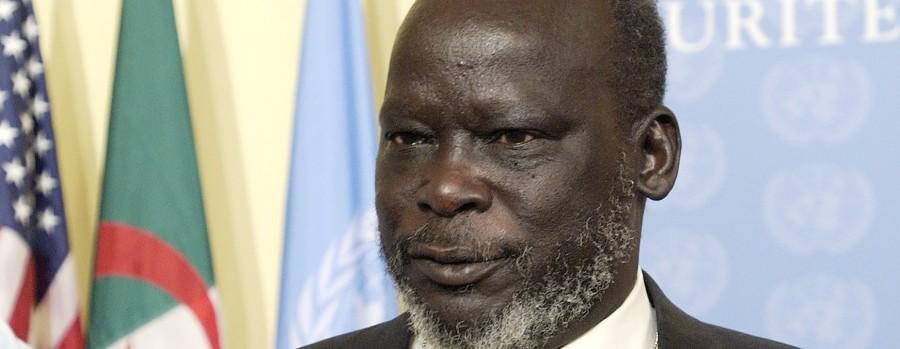

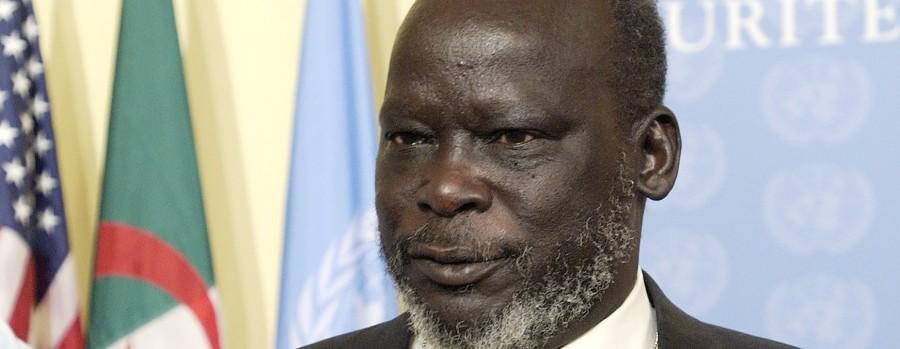

John Garang Remembered 10 Years On – By Mawan Muortat

On July 30th South Sudan celebrated Martyrs’ Day, an official remembrance day for those who died in the national liberation wars. That date was purposely selected because it is the day on which John Garang, South Sudan’s most iconic leader, was killed in a mysterious plane crash.

On July 30th South Sudan celebrated Martyrs’ Day, an official remembrance day for those who died in the national liberation wars. That date was purposely selected because it is the day on which John Garang, South Sudan’s most iconic leader, was killed in a mysterious plane crash.

It was a day that South Sudanese thought would never come. Millions had pinned their hopes on him. Khartoum exploded in violence as grieving southern Sudanese, convinced of the government’s complicity in his death, went on a rampage and clashed with northern Sudanese and the police.

The SPLM leadership intervened to urge calm. The SPLM high command convened an emergency meeting at New Kush, a remote south-eastern SPLA stronghold, and Salva Kiir Mayardit was quickly and unanimously elected as the new leader.

John Garang is believed to have been born on 23 June, 1945, to father Mabior Atem Aruai and mother Gak Malwal Kuol in the village of Wangulei, Twic East County, Jonglei State. He spent his early childhood in the challenging and strict surroundings in which rural Dinka boys were reared.

He might never have attended school had it not been for the fact that his uncle, who worked at the Secondary School in Rumbek, wanted him to enrol in formal education. However, Garang, like any other boy of his generation, was unenthusiastic.

He was determined to remain with his siblings, tending to the family herd. But his uncle prevailed over him and Garang was admitted to a primary school in the town of Tonj, about 75 miles from Rumbek, but a good 700 miles from home.

Garang embraced education. His colleagues recall him as a good student with an aptitude for mathematics. The 1960s were years of political awakening for South Sudanese students. They wanted more rights for South Sudan and an end to what they saw as the Arabisation and Islamisation policies of the Khartoum government.

General Ibrahim Abboud, head of the ruling junta, brought in draconian measures to curb the protests, but these only exacerbated the situation. Many students including John Garang, then at Rumbek Secondary School, were expelled..

Garang went on to complete his schooling in Tanzania, then joined Grinnell College in Iowa, USA, to study economics, before returning to Africa and the University of Dar-es-Salam. A short stint with the Anyanya, the southern liberation movement, in 1971 led to further studies in Israel, this time in military sciences.

Upon his return, the Addis Ababa Peace Agreement between the Anyanya and the government of Sudan was signed, and Garang alongside other Anyanya combatants joined the Sudanese army.

The 10 year lull in fighting allowed Garang to pursue his academic and military interests. He added a PhD and several other military qualifications to his portfolio and went on to teach at several prestigious Sudanese educational and military institutions.

A capable officer and a keen revolutionary

John Garang’s sudden ascendance to power from relative obscurity soon after the 1983 Bor and Ayod mutinies took many South Sudanese and Sudanese by surprise. Observers of Sudanese politics, however, knew of him as a very capable officer and a keen revolutionary who was being closely watched by Jaafar Numeri’s government.

Among the former Anyanya, he was known as a member of a secret group of southern officers who were planning to return to war with the north. Another member of the ring was a quiet Military Intelligence Corps officer by the name of Salva Kiir Mayardiit.

Garang represents different things to different people. He was a crossover politician who for many in the north was the leader Sudan deserved but never had.

In his first and last rally in Khartoum, in 2005, the highways into the city were gridlocked and an unprecedented one million strong crowd jostled to hear him. That he didn’t get to address the people that day due to an alleged technical fault cannot detract from the fact that the event marked a unique moment in Sudan’s history.

The consensus in the north these days, at least among those opposed to the Islamist government, is that if it hadn’t been for the hard-line National Congress Party (NCP), an associate of Garang’s would have become the President of the Sudan and the south would not have seceded.

That might be so; but the fact Garang fought three successive governments prior to the arrival of the NCP casts great doubt on the claim that the NCP was the sole villain. Closer to the truth is the view that the NCP spoke for an un-ignorable section of northerners.

To this group, Garang and the SPLM represented an existential threat to the dominance of the riverian Arab tribes. Their decision to reject unity as offered by the SPLM and so to let go of the south should be viewed as an act of defence than of sacrifice, and of defiance rather than defeat.

A unique politician

Garang’s political and military abilities are rarely questioned. What is poorly understood are the influences that led him to acquire and champion the political ideas that later set him apart from the other Sudanese leaders of his generation.

This will be tackled by his biographers of whom there will be no doubt many. But we can safely suggest that leaving South Sudan at a relatively young age would have challenged his early ideas and stretched his horizons. Other influences must include studying in the strife-gripped late 1960s America and in Mwalimu Nyerere’s Afro-socialist Tanzania.

John Garang was not the first unionist South Sudanese politician. Joseph Garang of the Sudanese Communist Party derided the idea of southern separation. Similarly, William Deng Nhial, founder of the SANU party, preferred a federated Sudan and believed the south was too underdeveloped to manage alone as an independent country.

Garang’s appeal was his success in blending his adherence to the concept of “unity in diversity”, with the belief that this could not hold without the consent of the south. He persistently urged the South Sudanese to stop viewing the Islamic-Arab culture of the north as a threat, but to welcome it as an enriching element of Sudanese society as long as all the cultures and faiths of Sudan were afforded equal status.

Garang’s appeal was his success in blending his adherence to the concept of “unity in diversity”, with the belief that this could not hold without the consent of the south. He persistently urged the South Sudanese to stop viewing the Islamic-Arab culture of the north as a threat, but to welcome it as an enriching element of Sudanese society as long as all the cultures and faiths of Sudan were afforded equal status.

Garang also argued that the enemy wasn’t north Sudan or the northerners but the existing political system in the country. By downplaying the role of ethnicity and race in the conflict and emphasising the role of ideas, the SPLM was able to shift its attention to its political vision as it now viewed itself as a future government.

It began to debate and address key social and economic issues, including gender equality, rural development and international trade. This had never happened before in southern politics.

Garang dispatched expeditions to the Nuba Mountains, Blue Nile, Darfur and other parts of north Sudan to spread the SPLM message. Volunteers from these regions soon travelled south where they received military training and gradually the war moved north.

The confinement of the war to the geographical south has been turned on its head, and Garang’s insistence that there was no such thing as a “southern problem” but a “problem of Sudan” has become a reality.

Many observers regard the CPA as Garang’s greatest achievement. Whether it should be deemed a success or a failure is a matter for debate. The secession of the South is regarded as a negative outcome by some.

In this regard we might be better served by reminding ourselves of how Garang actually presented the CPA to the South Sudanese: “I and the SPLA have brought to you the CPA in a silver plate and it is you to determine your own fate; whether you remain a second class citizen in your own country or not”.

And if he hadn’t died?

No discussion of a figure of John Garang’s stature can be had without addressing the question of how things might have fared had he still been alive.

Garang could not prevent south on south violence during his reign and there is no reason to believe that he would have circumvented the violence that has haunted the country since the signing of the CPA. On economic development, fiscal control and the management of the SPLM, real progress might have been accomplished.

It is difficult to put a positive spin on the tarnished image of the SPLM today. Credit must be given where it is due however. The SPLM’s success in handling the deceitful NCP throughout the long and thorny interim period will go down in South Sudan’s history as an example of great team work, determination, competence and prudent leadership.

President Kiir’s so-called big umbrella or big tent policy of pardoning, accommodating and rehabilitating the endless flow of South Sudanese spoilers, including many utterly destructive politicians and armed militia groups, must be praised by everyone. The fact that it unraveled in December 2013 should be attributed to the complexity of the undertaking rather than the lack of will to address it.

Nonetheless, and even with all the best intentions in the world, no one can deny that there have been many major failures since Garang’s death. As the party in government, the SPLM has failed to reach its key development goals in the areas of education, health and infrastructure development.

Corruption has taken hold in all levels of government. Millions of dollars of public money have been syphoned off to private foreign bank accounts or invested in properties, land and other overseas assets. Journalists have been silenced and law enforcement agencies seem incapable of stopping the widespread lawlessness.

This abysmal record in itself is not unique to the SPLM or South Sudan of course. It is the outcome the world has come to expect from nearly every post-independence African government. But when measured against the uniquely desperate needs of the country or the vision and pledges of John Garang and the SPLM, these results can only be described as soul crushing.

On the war front, peace remains as remote as it was since it began 18 months ago. The two sides have not even identified a single major area of agreement, let alone begun to tackle areas of disagreement.

The SPLM-led government finds it anathema to accept a peace deal that would install Riek Machar as a successor of President Salva Kiir. Machar is not only accused of masterminding the current crisis but is also blamed for setting back Garang’s military campaigns against Khartoum when he switched sides in 1991.

The South Sudanese public is however desperate for peace and the pressure is more on the SPLM- led government than on the rebels to find a peaceful resolution to the crisis.

As South Sudan remembers John Garang and all the martyrs, concern is growing for the SPLM and its dented reputation. The SPLM does not have a serious challenger and will continue to dominate South Sudanese politics for many years to come. This would be excellent for South Sudan if the SPLM was efficient, strong, united and committed to its vision, but a tragedy otherwise.

If the return of the former detainees to Juba means anything at all, it should be that the SPLM leadership has now a new opportunity to reverse the party’s fortunes. Failing to achieve this would be a terrible betrayal of the nation – and of Garang and everything he lived, worked and died for.

Mawan Muortat is a South Sudan commentator and IT analyst based in London. He can be reached at [email protected]

Well written….a little bit unfair to Machar, but well written all the same. This is probably the best columnist for this magazine!

Very educational indeed, I did enjoyed reading it with the facts.

Since August 2015 when this was written ,there have been many developments.A peace deal was signed and security arrangements were agreed upon.Machar will now return to Juba and the implementation of the next phase of the IGAD peace plan will proceed.This is very encouraging.Africans have found an African solution.Some months ago there were calls for putting South Sudan under UN trusteeship,or even asking the Great powers to help rule it.

I commend Mr Mourtat’s acknowledgement that there were tremendous failures and corruption.

I am disappointed that he still upholds the personality cult of Garang. Politically,he was a centraliser who controlled everything .He did not accept other opinions and those who objected were either imprisoned or killed.He kept able politicians away by insisting on them to join as soldiers(and implicitly obey orders without discussion).He also refused to negotiate in good faith with the democratically elected government of Sadiq AlMahdi in 1986.

The idea of New Sudan based on inciting the periphery is not his own.It was expressed by Ben-Gurion as a way to break up the cohesion of the those supporting the rights of the Palestinians.

Those who gathered to greet him in Khartoum were not necessarily adherents of his New Sudan vision.They were rejoicing the hope of peace.

The New Sudan Vision has died with John Garang According to Professor Peter Woodward.Those advocating it now in South Sudan are advocates of expansionism and proxy war.The question of how to handle relations with the Sudan needs to be answered positively.Respect of each others sovereignty (as the US envoys have said to Juba) not adventures like the occupation of Heglig or the naive claim that Kush was Southern Sudanese.Kush is now used to collect money in the US for certain South Sudan organisations!.Kush is Nubian,North Sudanese.

There is the need for co-operation to make South Sudan a great nation and a pride to the black people worldwide.