We need to decongest Africa’s prisons urgently. For everyone’s sake.

There are three steps governments across Africa can take to avoid COVID-19 spreading through over-crowded prisons.

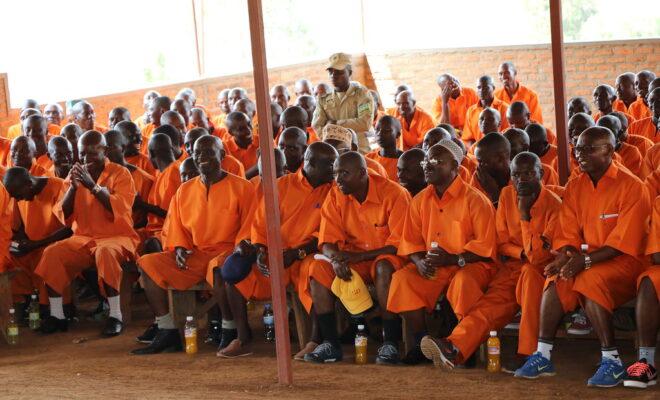

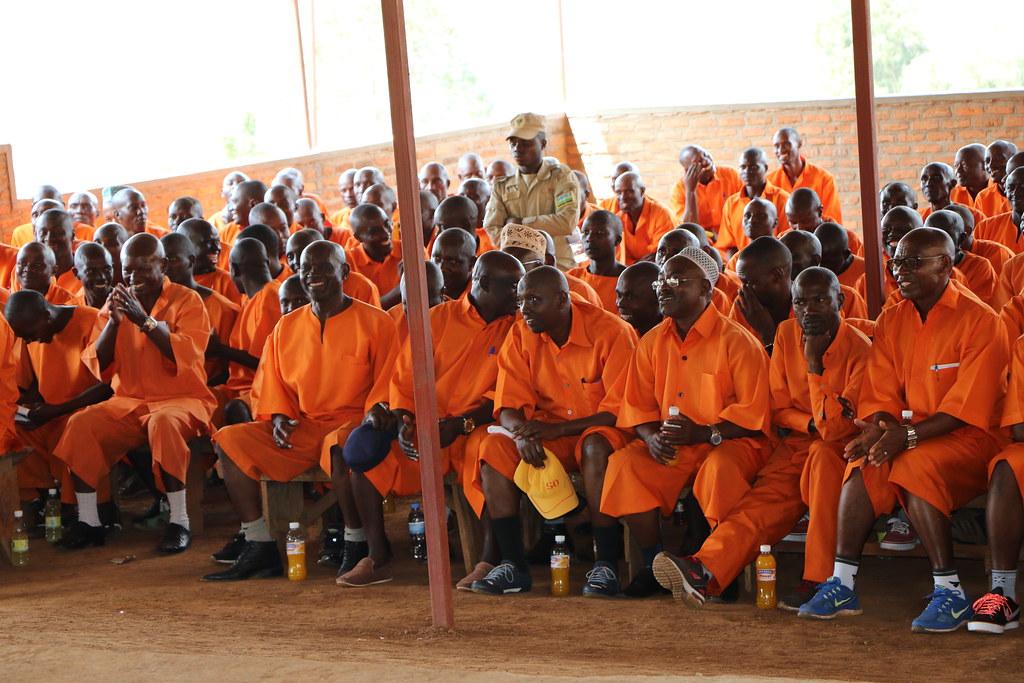

Inmates of a prison in Rwanda. Credit: LVEMP II Rwanda.

Read all our COVID-19 coverage

Across the continent, prisons are overcrowded. They exceed capacity and are under-resourced. In South Africa, one of the continent’s wealthiest countries, prison overcrowding stood at 37% in March 2019 with 162,875 detainees for just 118,572 bed spaces.

People in detention are particularly vulnerable to the COVID-19 outbreak. Prisoners live in confined conditions with others for prolonged periods. Hygiene and health care are difficult to access in detention centres worldwide, and even more so during a pandemic. And the transmission of diseases in overcrowded facilities is rife, placing the lives of both prisoners and staff at risk. The coronavirus has already started to spread in prisons across the world.

Because of these serious risks, the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, Michelle Bachelet, has called on governments to take urgent steps. She has urged them to reduce prison populations, protect people in places of detention, and prevent uncontrollable outbreaks.

These proposed measures are not new. They are in line with existing international standards (such as the UN Nelson Mandela Rules, Bangkok Rules, Tokyo Rules) and reflected in the African Commission on Human and People’s Rights regional guidance (such as the Luanda Guidelines). For several years, countries have been encouraged to reduce prison populations. Now with COVID-19 spreading fast, these measures need to be prioritised.

Some countries are slowly starting to take action. Ethiopia pardoned more than 4,0000 prisoners whose release dates were soon or had been given sentences of less than three years for minor crimes. Iran released over 85,000 prisoners. France’s Ministry of Justice is asking for short-term prison sentences to be delayed, reducing the number of new prison admissions from 200 a day to 30. And Ghana recently granted amnesty to over 800 prisoners, most of whom are first offenders.

Over 30 civil society groups across Africa, from Sierra Leone to Uganda, are calling for similar measures to be implemented in their own countries. There are three key steps that governments should take.

1) Release these four groups

Governments should review cases of people in detention and seek to release the following four groups.

Firstly, people held in pre-trial detention, particularly those for minor or low-risk offences. For this group, alternatives to pre-trial detention such as bail or electronic tagging should be provided. Releasing this group alone would have a huge impact. In about half of African countries, more than 40% of the prison population are pre-trial detainees.

Secondly, pregnant women and women with children should immediately be considered for release. This can be done through various measures such as bail, early release, pardons or suspended sentences.

Thirdly, at risk populations such as elderly prisoners or those with underlying health issues should be released.

And fourthly, individuals sentenced for minor, low risk offences – particularly those who have 18 months or less remaining of their sentence to serve – should be freed.

By reducing the prison population, these measures will not only help to protect detainees but detention staff, lawyers and others working in the criminal justice system.

2) Stop arresting people for minor offences

The police have a vital role to play in ensuring that police stations, courts and prisons are not overcrowded. They can help to reduce the burden on government institutions at this crucial time.

To do this, the police should not arrest people for minor offences. Where strictly necessary, non-custodial measures should be used instead such as diversion, a warning or bail.

3) Protect detainees’ human rights

Prisons need to ensure that the human rights of those in their custody are respected, that people are not cut off from the outside world, and – most importantly – that they have access to information and adequate healthcare provision.

Despite resources being stretched, protective measures should be put in place so that those in detention can still receive access to legal advice and representation. Where this is not possible in person, prisons should provide for unfettered, free access to confidential telephone lines to contact lawyers.

Measures should also be put in place to ensure that organisations can continue detention monitoring. The World Health Organisation has stressed that the COVID-19 outbreak must not be used as a justification for objecting to external inspections. Independent international or national bodies with mandates to prevent torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment must still be able to monitor detention centres.

Many countries on the continent have been quick to respond to the pandemic and implemented various preventative measures, such as school closures and border closures. Any strategy to reduce COVID-19 will be ineffective, however, without taking urgent steps in the criminal justice system.

Audrey kemeugne