“This is not the life I wanted”: Child brides rise among Cameroon refugees

Child marriages are often driven by economic pressures, and COVID-19 has hit the most vulnerable the hardest.

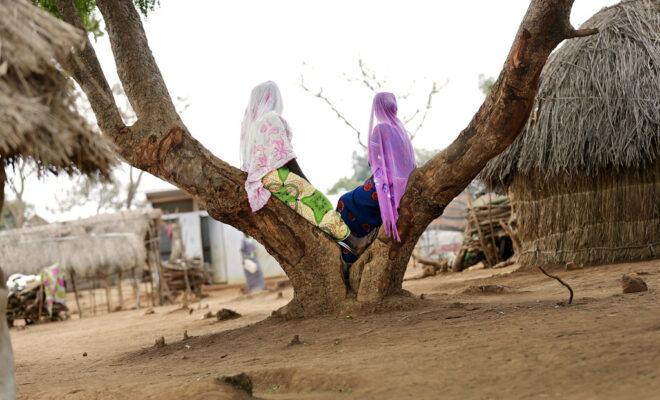

Women from Cameroon in a refugee camp. Credit: UN Women/Ryan Brown.

As Mura turned 16 years old this February, she and her family were struggling through thick forests and grasslands. They had fled the bloody separatist war in Cameroon and were looking to seek refuge in southeast Nigeria.

When they finally arrived safely in Cross River state, they decided to stay with a distant relative in the town of Obanliku rather than head to a refugee camp. As they started to rebuild their lives in this arid district, Mura’s parents tried to find ways to support the family. They settled on selling snacks. Mura’s mother made them at home and her father sold them to students from a kiosk outside the secondary school compound. Mura and her two sisters helped their mother and looked forward to attending that same school when they could enrol.

After a traumatic few months, the family were finally beginning to find some stability. But then everything changed. In March, the Nigerian government announced the closure of schools to contain the spread of the coronavirus. The family’s source of income was no longer viable.

It was in these desperate times that Mura’s father was approached by a local crop farmer. The 50-year-old man offered to marry Mura. If his proposal was accepted, he would pay a bride price of $80. Her father accepted and his teenage daughter was married off to man more than three times her age.

“It was not what we wanted for our daughter, but we didn’t have a choice,” Mura’s mother told African Arguments. “We wanted the money to take care of Mura’s siblings.”

Mura says she is treated like a “slave” by the “old man” who is now her husband. She is relieved that she is allowed to spend time with family but says she finds it difficult to forgive her parents who, she says, always intended to marry her off.

“Yes, the coronavirus made them make the decision quicker, but it had always been in their plans,” she said. “They had told me since I was 15 that I was ripe for marriage as my mother married my father when she was also 15.”

“Money wives”

Mura’s story is far from unique. According to campaigners, 31% of girls in Cameroon are married before they turn 18, and 10% are married before they turn 15. In Nigeria, the figures are even more alarming with 44% of girls being married before the age of 18, and 18% before the age of 15.

Many are concerned these rates have increased even further due to the pandemic. In April, the UN Population Fund (UNFPA) warned that economic hardships as a result of COVID-19 could lead to 13 million more child marriages worldwide. Some countries such as Malawi and Ethiopia have already reported surges in child marriages since the coronavirus hit.

These same trends are also being seen among the tens of thousands of Cameroonian refugees in Nigeria.

“There is concern that child marriages involving Cameroonian refugees are growing quietly,” says Salome Gambo, a senior researcher with Caprecon Development and Peace Initiative, which supports victims of human trafficking and sexual abuse in refugee communities. “Unfortunately, such marriages are difficult to track because parents quietly give away their daughters and many who do so don’t live in official refugee camps.”

Both Nigeria and Cameroon have ratified international conventions and passed national laws that prohibit marriage below the age of 18. But many of these provisions have not been applied or enforced.

“Many Cameroonian families still cite the old law that allowed girls under 15 to be married,” says Eno Edet, a human rights lawyer who works to protect victims of child marriage in Cross River state. “This low level of awareness is not just peculiar to the western regions but all across Cameroon.”

In Obalinku itself, there is a long tradition of girls – often referred to as “money women” or “money wives” – being married off to men as old as 90 in exchange for food, livestock, cash or to settle debts. The custom is particularly common among the Becheve people.

“This culture is part of the Becheve history and that makes it difficult to put an end to it,” says Magnus Ejikang, a local chief in Obalinku. “There are many Cameroonians who have come here and have embraced the culture.”

Gambo adds: “Many here see anti-child marriage campaigners as enemies who are out to destroy the culture.”

Economic pressures

Child marriage is not just a question of tradition, however. The families that embrace the custom tend to be poor and struggling like Mura’s parents. This is why many believe the economic hardships caused by lockdown restrictions are leading to a rise in the practice.

The livelihoods of Cameroonian refugees in Nigeria were already precarious to begin with. Around half live in UNHCR-built settlements where they receive cash-based interventions (CBI) of N4,600 (about $10) a month. The rest live across host communities, mostly in Cross River State, far away from the settlements and without any external support. In these difficult situations, child marriages can be seen as effective ways to make ends meet.

“Tradition makes it easy,” says Gambo. “But the desire to take some pressure off and gain materially is what drives these families.”

These pressures are only increasing. They prompted the marriage of Mura and many more, with life-changing consequences for those involved.

Helen, for instance, fled the same town as Mura’s family. This May, the 17-year-old girl was married off to her father’s employer, a 59-year-old livestock farmer. Her bride price consisted of a couple of goats and about $50.

“Sometimes, my father couldn’t afford food for us,” Helen told African Arguments. “I know he wanted me to get married to ease the pressure on him, but that wasn’t what I wanted for myself…I told my father I wanted to complete my education first before getting married but he threatened to disown me if I didn’t follow his orders. ”

For Helen, Mura and many other girls, the situation is desperate. Dire economic need is adding pressure on families while long-held local tradition has normalised the practice. In this context, Helen only sees change as coming through official enforcement.

“The government has to be serious in making sure that girls can say no to child marriage,” she said. “No girl should be allowed to get married against her will…This is not the life I wanted.”