Debating Ideas is a new section that aims to reflect the values and editorial ethos of the African Arguments book series, publishing engaged, often radical, scholarship, original and activist writing from within the African continent and beyond. It will offer debates and engagements, contexts and controversies, and reviews and responses flowing from the African Arguments books.

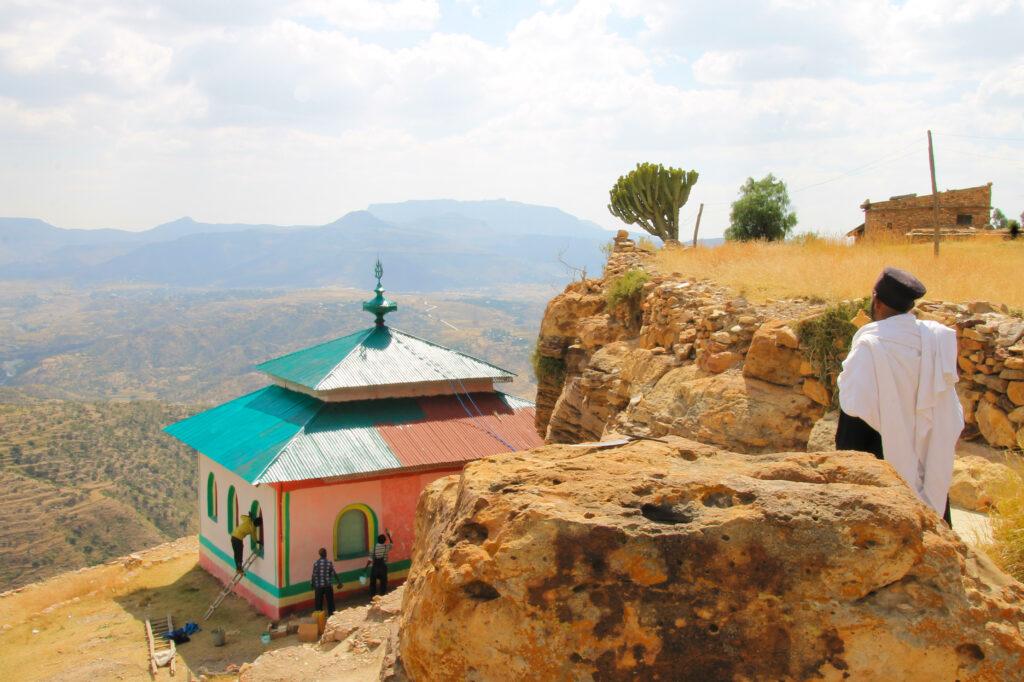

A monk in Tigray stares into the mountains that separate Ethiopia from Eritrea. Credit: David Meffe

In March 2020, Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed made an unthinkable announcement: national elections planned for August were postponed until 2021. At least. The country’s fledgling democratic infrastructure couldn’t safely handle the ballot amid Covid-19 restrictions. The vote would have to wait – it was in everyone’s best interest.

But for the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF), it was a final affront to regional sovereignty, another sign that Abiy intended to use the pandemic to cling to power beyond his September mandate. After all, the people had not elected Abiy. These elections were to be Ethiopia’s first real vote in decades, the centrepiece of an ambitious reform agenda and transition to inclusive democracy to halt the civil and ethnic unrest that had brought the country to the brink of Balkanization. The integrity of the constitution and ethnic federalism were at stake.

The TPLF had already been left out of the new ruling Prosperity Party, so it didn’t take long for them to make their own announcement: they would hold elections as planned and take their chances with the virus in defiance of Addis Ababa. Despite Abiy declaring the September vote illegal, Tigray succeeded in conducting a ballot with social distancing and other mitigation measures in place, with the TPLF securing a resounding victory in the process. The tanks soon rolled into Tigray, laid waste the regional capital Mekelle, and sent tens of thousands fleeing into neighbouring Eritrea and Sudan to escape civilian massacres.

Let’s be clear: Covid didn’t cause the crisis in Ethiopia. Tensions between Tigray, the central government, and the surrounding regions go back decades, and were at the heart of the mass protest movement that brought Abiy to power in the first place. Instead, Covid accelerated an inevitable showdown that turned a charismatic Nobel Peace Prize winner into a warmonger, and the kingmakers of the old regime into defiant insurrectionists. It won’t be the last time the pandemic sparks predictable humanitarian catastrophe.

Covid-19 represents the largest cross-cutting, socio-economic upheaval to affect Africa in decades. But on paper, infection and death rates look good enough, almost promising. Was it the young, isolated population in rural communities? Experience in pandemic control and contact tracing with Ebola and Yellow Fever? Unreliable data? The why is peripheral, though international media were quick to tout the African miracle. The real question is: what next?

Death rates represent only a sliver of the pandemic’s unseen impacts on fragile livelihoods, socioeconomically vulnerable groups like migrants and women, and other efforts at democratisation in the Horn. Researchers in the field describe poor testing, refusals by doctors to diagnose Covid post-mortem, and an overall sense that large data provided by national and regional governments deliberately obfuscates the dire situation in areas affected by armed conflict, shrinking civic space, endemic poverty, and low access to health services.

Live infection tallies may be reassuring metrics in stable Western economies, but the real everyday impacts of the pandemic in Africa are pronounced on precarious livelihoods. Traders, domestic labourers, taxi drivers, and others pillars of the informal sector remain heavily constrained in much of the Horn. Transportation restrictions have severed food supply chains built on rural-to-urban commerce routes, notably in landlocked countries like Ethiopia, Uganda, and South Sudan. Not that this affects the region’s political elites, who can always rely on dependable methods of enforcing unpopular policies.

Long-distance traders transport goods across the Afar region. Credit: David Meffe

Authoritarian governments have exploited pandemic prevention to legitimise state brutality commonplace before the outbreak. Rights groups in Uganda alleged that the government’s heavy-handed enforcement of lockdown measures resulted in more deaths than the virus itself, with military forces violently clearing markets and other public places in viral videos. In May, nearly 10,000 people were forcibly evicted from informal settlements in Nairobi, despite the Kenyan government’s pledge to halt low-income housing expulsions during the pandemic.

Virus containment helps justify undue restrictions on inconvenient freedoms of assembly and expression; necessary measures to protect people from themselves. Notwithstanding that using violence to impose public health goods on subjects supposedly resistant to common sense is deeply rooted in colonial regimes, this irony seems lost on regional powers happy to lay the real burden on vulnerable scapegoats like minorities, migrants, and women.

Pandemics disproportionately affect religious and ethnic minorities who often live in densely populated communities due to shared socioeconomic disparities, institutional racism, or de facto residential housing segregation, making it difficult to practise social distancing or adequate domestic hygiene. This applies double for refugees and migrants, which most countries in the Horn of Africa were already struggling to manage pre-Covid. They generally make their living in informal or irregular sectors and enjoy no labour protections or emergency relief benefits. Moreover, cultural and language barriers often leave displaced peoples unaware of national Covid guidelines, reinforcing structural inequalities and negative social attitudes that already stigmatise them as unwelcome disease-carriers.

Informal labourers mine for salt in the Afar Desert east of Tigray. Credit: David Meffe

Compound this for women, who have also been disproportionately hobbled by pandemic constraints on the informal economy. Lockdown restrictions have increased rates of sexual and gender-based violence, as the closure of public spaces confines survivors with their abusers, cuts off access to shelters, and exacerbates existing barriers to justice. The thousands of women and other refugees currently fleeing Ethiopia will only add to these negative trends.

Ethiopian refugees in Sudan

Covid is by no means the root cause of inequality in the region, but it contributes to a spiralling of knock-on effects that have already stymied other efforts at peacebuilding and transitional justice in the Horn’s more precarious states. In June 2020, Somalia’s electoral commission announced that not only would the September national elections be delayed by 13 months due to insecurity, flooding, and Covid-19, the historic ‘one person one vote’ ballot would be scrapped in favour of a return to the system of electoral colleges, albeit with slightly more delegates. Already scarce resources for election monitoring and civic education are being reallocated to the pandemic response, hobbling the kind of investment needed for successful universal suffrage.

A woman prepares food for sale on the streets of Jijiga in Somali region. Credit: David Meffe

Civil society groups have similarly warned that Covid might be used to scuttle the transition to civilian rule scheduled to occur in the next two years in Sudan. The country is already in dire economic straights due to low oil prices, the closure of shipping ports, and lingering international sanctions that have led to massive hyperinflation and rampant unemployment. The government’s slow response to the pandemic could give the military just the public health excuse it needs to seize power and become another failed revolutionary autocracy like Egypt.

These threats to regional peace and security extend to civil society activists and human rights defenders who brace weak democratic institutions, like in South Sudan where monitors and researchers help implement peace agreements and report ceasefire violations. South Sudan’s ruling elites might also be tempted to use Covid to justify their existing lack of will to implement transitional justice mechanisms mandated under the 2018 revitalised peace deal, notably the Hybrid Court. International funding for development, democratisation, and research is already being slashed in response to the global economic downturn, making oversight of these negative trends even more difficult.

In response, grassroots solidarity networks offer an avenue for donors to increase their support to African human rights activists and fill the gaps left by absent states, allowing international organisations to implement projects amid restrictions on travel and field work. Having local actors conduct health advocacy and share information at the community level can also be a resource for governments who struggle with public information management, especially with migrants and refugees. These community actors would be uniquely positioned to monitor Covid-related human rights abuses in otherwise isolated communities.

International solidarity through debt relief must also be part of any efforts at rehabilitating African economies and maintaining political stability to promote open societies. In April, the UN Economic Commission for Africa recommended a temporary debt standstill for two years so African countries can redirect resources towards fighting the pandemic. This is especially important for countries like Egypt and Djibouti, whose debt-to-GDP ratio makes growth all but impossible. Debt relief could also help address gender inequality and lift the burden of poverty from women. In April, China expressed a willingness to provide Africa debt relief, but not outright forgiveness – what implications this will have for their Belt and Road Initiative in the Horn of Africa are yet to be determined.

Streetside coffee sellers in Axum (Tigray). Credit: David Meffe

So while the fighting rages on in Tigray, it’s important to remember that Covid doesn’t cause wars or social inequality, but has the potential to catalyse and bring to a boil negative trends that have simmered for decades in fragile states. Africa will be the last to receive any vaccine rollout, so real pandemic recovery needs to be about more than just counting the dead. It must address the compounded social challenges posed by ethnic and gender-based marginalisation, stagnant economies, and the region’s deeply unsustainable political marketplace. Otherwise, the enormous gains made in Ethiopia and Sudan will recede, while Somalia and South Sudan will disengage from the stakeholder engagement needed to prevent a return to all-out civil war.

Africa may have avoided the inflated death tolls of the West, but the war in Ethiopia is the first real symptom of Covid in a region where the living may suffer its effects more acutely than the dead.