Debating Ideas is a new section that aims to reflect the values and editorial ethos of the African Arguments book series, publishing engaged, often radical, scholarship, original and activist writing from within the African continent and beyond. It will offer debates and engagements, contexts and controversies, and reviews and responses flowing from the African Arguments books.

Chad holds funeral for late President Idris Deby Itno. Credit: DW

Perhaps the most striking thing about Idriss Deby Itno’s death is that he left power as he came to it – at the barrel of a gun. Chad has never had a peaceful democratic handover of power, and if anyone was wondering if things have changed during his time in power, events over the last week seem to have shown otherwise.

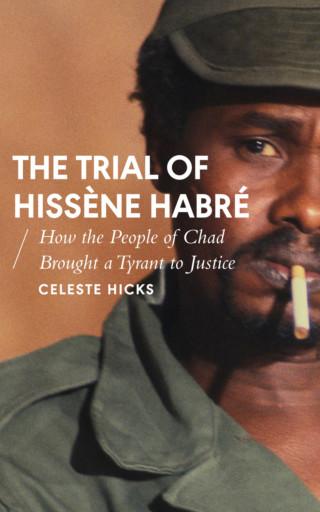

In 1990, aged 37, Idriss Deby overthrew Hissène Habré’s brutal regime. Deby, a Zaghawa from Chad’s north-eastern desert border with Sudan and disgruntled former army chief; Habré, from the Toubou ethnic group which hails from Chad’s northern desert border with Libya, forced to flee to Senegal when Deby’s troops arrived in the capital. Today, 31 years later, Habré sits in a prison cell in Dakar after being jailed in 2016 for crimes against humanity during his rule. (Who knows what is going through his mind as he contemplates the death of the younger man.)

The FACT (Front for Change and Concord in Chad) rebel group which led the lighting raid on northern Chad, culminating in the deadly clashes north of Mao last weekend in which Deby died, is led by Mahamat Mahdi Ali. He is also from Habré’s Toubou (or Gorane) ethnic group.

In some ways, nothing has changed. In others, everything has.

In his 30 years in power, Deby saw off at least five similar rebellions. The most serious two occurred in 2006 and 2008, when rebels from the FUC (United Front for Change) and the UFDD (Union of Forces for Democracy and Development) groups reached the streets of N’Djamena. The fighting was intense and terrifying, as Deby’s elite soldiers battled eye to eye with the rebels in the roads leading up to the presidential palace. The rebels’ tactics – driving at incredible speed across the desert, in lightly armed pick-up trucks mounted with machine guns, often at night with the headlights switched off – were surprisingly successful in the early days when the ANT (National Army of Chad) was similarly armed.

And then in 2009 the game suddenly changed. Using billions of dollars of oil money earned since 2003, Deby invested heavily in military equipment – APCs (armoured personnel carriers), helicopters, Sukhoi jets. When the UFR rebels tried again in 2009 at Am Dam, they were obliterated.

On Tuesday morning, the rebels looked as if they would again be stopped in their tracks. Either by the better equipped ANT, but if that failed, most analysts expected that France would have to step in as they had done against the UFR (Union of Resistance Forces) near Faya Largeau in early 2019.

But the wild card was Deby’s death.

It’s no surprise that he was at the front, commanding the troops, and likely scaring them into remaining loyal. In 2020 he was at the front directing the battle against Boko Haram militants who had inflicted a terrible defeat on the ANT in the Lake Chad region. He was reportedly a capable general, known as the ‘Great Survivor’. But, of course, one day his luck was sure to run out.

For the last 15 years, analysts have pondered the question: “What happens when Deby dies?” Rumours about his ill-health, and at times reputed alcoholism, circulated. With so much rivalry in the corridors of power, defections in the army, family members vying for power, jealousy from other groups at how the Zaghawa had taken over business and government positions during those 30 years, the danger of an assassination could never be ruled out.

But Deby went on and on, and for the last ten years looked almost as if he really had secured his position. He became a reliable ally of the international community, and in particular of France in its Sahelian counter-terrorism policies. The ANT graduated from desert warriors to peacekeepers in Mali, and Chad’s diplomatic influence on the continent blossomed with Deby’s former foreign minister Moussa Faki Mahamat becoming AU Chair. The Deby family continued to enrich themselves and entrench their power thanks to Chad’s oil reserves.

Now Deby has gone, it’s interesting to consider whether the wild card really was that random. Perhaps it goes to show that really nothing has changed in Chad, where rival groups have been hacking it out in the desert for 60 years trying to gain power and influence. Deby’s son Mahamat now has a heavy burden. The dangers of a descent into bloody chaos, if every disgruntled rebel in Chad now grabs a gun and makes for N’Djamena, are very real.

But Mahamat also has a chance to show that there could be another way. Chad does have modest oil reserves which can buy some development; it is relatively stable compared to its neighbours, and it has a good reputation as a reliable partner which the international community recognizes. He could choose to break with that historical narrative and take the opportunity to stand aside as promised after a transition period, allowing for democratic elections to take place.

Only time will tell which path Chad will take.