“The guards had no compassion”: The migrants abandoned in Niger’s desert

Thousands of migrants are being seized in Algeria, abused and then left at Point Zero, a spot in the middle of the desert, often in middle of the night.

Three young men joke with each other to pass the time near the reception site in Assamaka, Niger, soon after being deported from Algeria. Because of COVID-19, all recently returned migrants are held here for a quarantine period of 14 days before being transported to Agadez. Credit: Mariama Diallo/MSF.

Safi Keita was four-months pregnant and making a living selling spices in Algeria the day the police arrived at her home. “The gendarmes broke down the door,” she says. “They took everything: money and phones. Then they took me to the police station.”

The following day, the Algerian police sent Keita, who is from Mali, to a detention centre. “They put us in crowded trucks – it was very cramped, there were many of us and no one was wearing a mask,” she recalls. On arrival, she was made to jump to the ground. “Being pregnant, it caused me stomach pains.”

Keita was held in insanitary conditions and with only bread to eat. “Although I was pregnant, I received no special treatment,” she says. “The guards had no compassion towards me or my physical condition.”

Four days later, she was taken with other migrants to the border between Algeria and Niger where they were dumped unceremoniously in the desert.

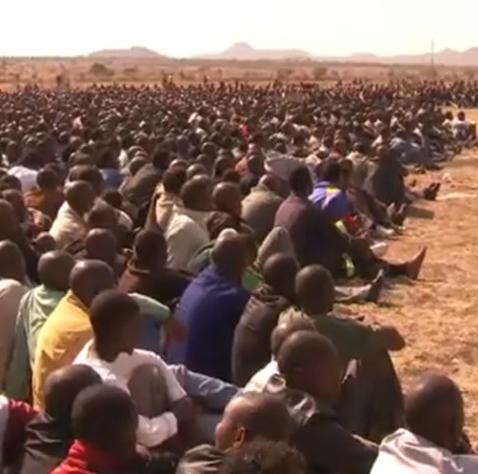

Keita’s experience was traumatic but far from unique. According to data collected by teams from Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF), 29,888 migrants arrived in the small Nigerien town of Assamaka, near the Algerian border, in 2019. Despite land border closures in March 2020 due to COVID-19, expulsions continued. 23,175 people were removed in 2020 and, as of mid-April, 4,370 migrants had been expelled so far in 2021.

Many of those forcibly removed report having experienced violence, including torture. In 2020, MSF teams provided medical care to nearly 1,000 migrants affected by violence and almost 2,000 migrants suffering from mental health problems.

According to testimonies collected from hundreds of migrants from Algeria to Niger, most are originally from West Africa and South Asia. They include young men, women, children, and the elderly. Some had lived in Algeria for years before being deported. Others had been travelling through the country on their way to Europe.

Many had similar experiences to Keita. They describe being arrested and then kept in detention centres – whether for days, weeks or months – before being forced onto buses or trucks by Algerian security forces. They were then dropped off at a place known as “Point Zero”, a spot in the middle of the desert between Algeria and Niger, often in the middle of the night. With nothing in their pockets and no map or directions, they faced a 15 km walk to Assamaka, the nearest settlement. Some reportedly got lost on the way and were never found.

Traoré Ya Madou’s harrowing story is typical. He moved to Algeria from Mali and had worked for six years as a painter before he was expelled. “We lived right on the site where we worked,” he says. “That morning, the Algerian police arrived. Usually, we’d give them money or resist and eventually the officers would leave. But that night, there were about 20 of them. They broke down the door and entered. They handcuffed us and transported us to the police station. I was there for 24 hours with nothing to eat. They searched us and took off our underwear – it was inhuman treatment. I had 2,500 euros on me and the officers took everything. They beat me so savagely that I had to go to hospital.”

As punishment for trying to resist arrest, Madou was reportedly taken much further into the desert than other migrants and had to walk for around four hours to reach Assamaka.

Human rights abuses

The stories of these individuals like Keita and Madou offer just a glimpse of what is happening on the border between Algeria and Niger. Since the Libyan uprising in 2011, the route through Niger and then northwards through Libya or Algeria has been the main migratory route from West Africa towards Europe. Policies designed to curb the flow of people have not prevented people trying to move but have simply increased the risks to them by criminalising their actions and violating their human rights.

At the 2015 Valletta Summit, European and African countries strengthened their border control systems and agreed to facilitate the return, voluntary or not, of migrants deemed to have moved illegally. As a result, migrants continue to be arbitrarily arrested, subjected to ill treatment, and returned to countries where they may face persecution.

“These arrests, detentions and expulsions by the Algerian government do not respect the fundamental principle of non-refoulement and are contrary to international human rights law and international refugee law,” says MSF head of mission Jamal Mrrouch. “It is essential to readjust these policies and guarantee humanitarian assistance and protection to migrants on the move, ensuring that local facilities in transit countries such as Niger can meet the needs of all.”

Lovely just what I was looking for.Thanks to the author for taking his clock time on this one.

Thanks for the article.Really looking forward to read more. Want more.