Debating Ideas is a new section that aims to reflect the values and editorial ethos of the African Arguments book series, publishing engaged, often radical, scholarship, original and activist writing from within the African continent and beyond. It will offer debates and engagements, contexts and controversies, and reviews and responses flowing from the African Arguments books.

Portrait of Zaga Christ ( Sagga Krestos) Giovanna Garzoni, 1635. Credit: Wiki Commons

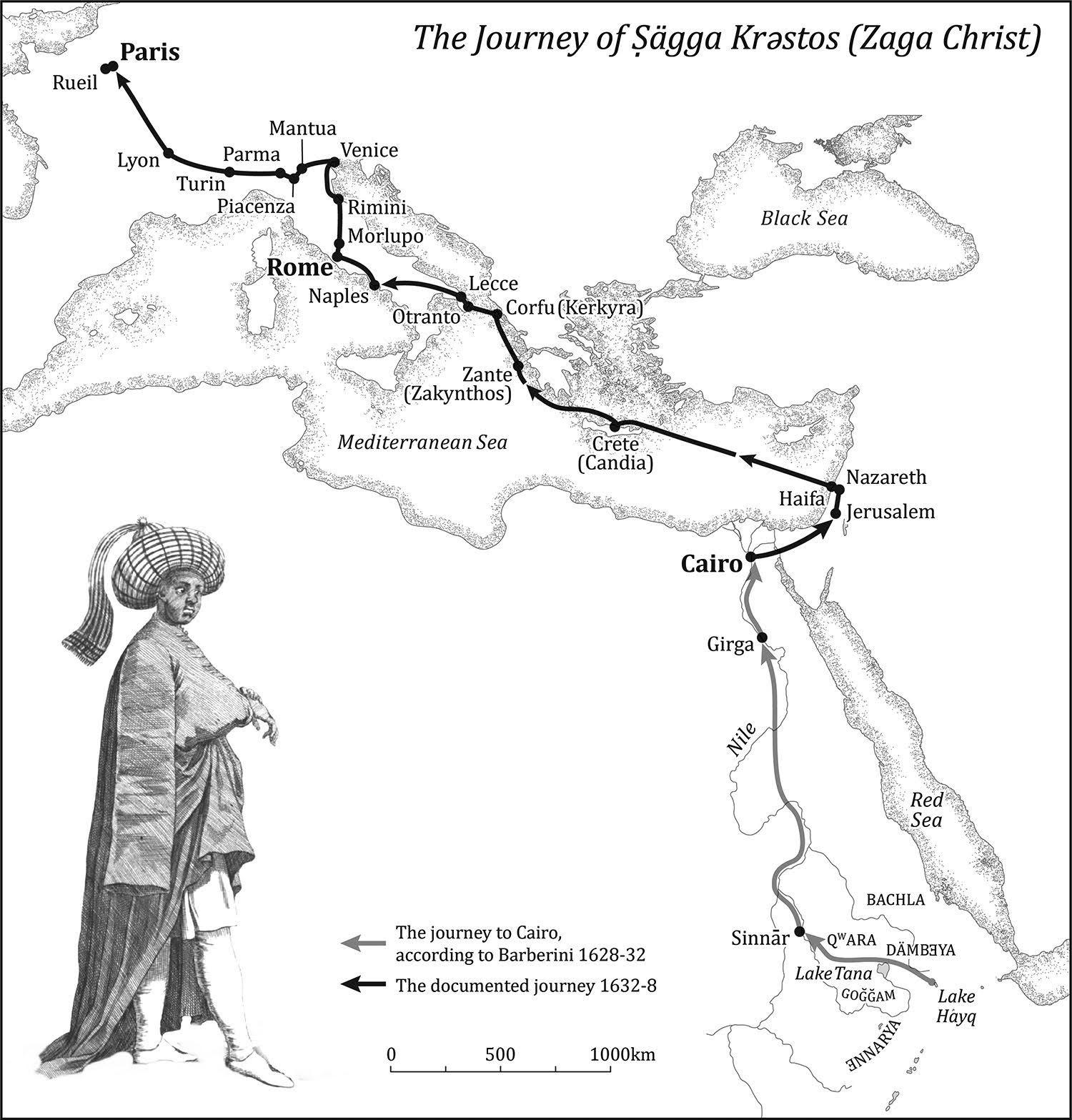

In 1632, a young African by the name of Zaga Christ introduced himself to Franciscan missionaries in Cairo, claiming to be the heir to the Kingdom of Ethiopia. From there, he travelled to Italy and France, where his impressive interpersonal skills, his interlocutors’ ignorance about Africa, and a favourable historical juncture, allowed him to be generously hosted and supported, despite his inability to prove his claim and growing doubts about its veracity. He would never return to Ethiopia, but die in Paris instead, hosted by Cardinal Richelieu, first minister of France. Zaga Christ’s journey produced a substantial paper trail: state officials, chroniclers, churchmen, and curious intellectuals wrote about him, and widely circulated newsletters published his obituary.

The most fascinating document about Zaga Christ’s experience is his own autobiographical statement, which he dictated to an anonymous scribe while in Rome. Here, the Congregation of Propaganda Fide, a sort of ministry of missions, sought to vet him before turning him into the cornerstone of a Franciscan mission to Ethiopia. The document is an intriguing medley of facts and fiction: it includes a believable genealogy and summary of recent Ethiopian dynastic history, both meant to bolster his claim, along with a fantastic account of his escape from Ethiopia, journey through the Nile valley to Cairo, and a verisimilar account of his sojourn in the Middle East and transit to Rome. Many versions exist and some can be traced to Zaga Christ’s own initiative: as he travelled across Italy and France, he shared his statement to introduce himself, and some of his acquaintances copied it. Once in Paris, he had it translated into French, published, and dedicated to the Queen of France, to obtain royal support for his stay.

Zaga Christ’s is a tale of imposture, but also ingenuity and survival: only in his teens when he reached Rome, he impressed many with his social skills, religious knowledge, and piety. His is among the best documented and unexpected experiences of an African in early modern Europe, but in no way unique. In the last two decades, scholars have documented the lives of many remarkable individuals who either hailed from Africa or were of part-African ancestry. Among them are Alessandro de’ Medici, the black duke of Florence, and talented Afro-Iberians such as the painter Juan de Pareja, the classicist Juan Latino, and the music theorist Vicente Lusitano.

My own work on early modern Ethiopian-European relations and the Ethiopian presence in early modern Europe contributes to this recuperation. I first became interested in the topic during my graduate work in the late 2000s, when I became familiar with colonial-era scholarship about Ethiopians in Renaissance Italy. Although its purpose was foul—casting Italian expansion in the Horn of Africa as benevolent and the natural continuation of older amicable fraternal relations—the sources unearthed were incredible. As a trained Africanist, I set out to read them from a perspective that could do justice to the primacy of Ethiopian agency: tellingly, the title of my very first article was The Ethiopian Age of Exploration (2010). In the ensuing years I produced a more comprehensive account of what I dubbed the Ethiopian-European encounter, along with articles on exceptional Ethiopians agents and their diasporic lives: the pilgrim and intellectual Tesfa Seyon, and Yohannes, better known as Giovanni Battista Abissino, the second African bishop in the modern history of the Catholic Church.

In recent years, other talented scholars have greatly enhanced our understanding of the early modern Ethiopian diaspora in Italy with more valuable contributions. Other historians have greatly advanced our understanding of the African presence in early modern Europe by adopting a social history approach, unearthing bits of evidence that, while insufficient for a comprehensive reconstruction of individual experiences, could be used to shed light on entire communities, for example in Florence and Venice, where Africans usually arrived in captivity, but could, at times, gain their freedom and integrate. No less important is the contribution of art historians, who have identified dozens, if not hundreds, of mostly nameless Africans in era paintings, which also testify to a much larger presence than normally thought. Among them is the black donor in Davide Ghirlandaio’s Coronation of the Virgin, whose wealth, social standing, and life trajectory we can unfortunately only imagine.

These stories nuance our understanding of African-European relations, and put to ridicule any understanding of the African presence in Europe as only postcolonial, let alone a threat to the continent’s identity. They also problematize facile understandings of race and racism in the early modern period: while most of these extraordinary individuals suffered different degrees of discrimination, for some, like Zaga Christ, being African was clearly what allowed him to survive and even thrive in the course of his journey. All in all, the African presence in early modern Europe can hardly be reduced to one of subjection and marginality.

Stories such as Zaga Christ’s should dissuade us from interpreting the African presence in early modern Europe through analytical categories developed to make sense of the colonial period, as they may give the account an anachronistic hue, if not lead us completely astray. A case in point is a postcolonial reading of Zaga Christ’s autobiography, which claims that Zaga Christ was the product of European imagination. As incredible as his European journey was, and regardless of the mendacity of his royal claim, Zaga Christ was a resourceful African agent who strove to chart his own future, as amply demonstrated by the archival evidence. Although, by the early 17th century, the perception of Africa and Africans had significantly deteriorated in the wake of the Atlantic slave trade, European ideas of racial difference had yet to crystalize and visitors like Zaga Christ could still press through porous racial borders and find ways to assert themselves despite their alterity. Decolonizing the historical discipline obviously means jettisoning stale colonial categories, but recovering pre-colonial experiences and the categories that defined them may be key to move towards a truly postcolonial understanding of our history.

All in all, there is no doubt that early modern Europe was not as white as our collective imagination purports it to be. While probably no other city reached the degree of diversity of Lisbon, where Africans seem to have accounted for one tenth of the population, evidence points to the existence of large African communities also in Amsterdam and London, just to name some locales that have attracted growing attention in recent years. While Europeanists have so far produced most of these African stories, one hopes that, as the field grows, the Mediterranean-European diaspora will attract Africanist, diaspora specialists, and world historians like its Atlantic-American counterpart.

*This blog piece was adapted from Africa’s journal article The narrative of Zaga Christ (Sagga Kresto): the first published African autobiography (1635), published under our Local Intellectuals series.

Quite interesting. A noteworthy effort by an “Africanist” European.

Good research sir!

Really fascinating story. On the time of Tsaga Christos (ጸጋ ክርስቶስ) journey to Europe 1632 Ethiopia was in civil war because of the Catholic missionaries conspiracy against the local Ethiopian Orthodox church.

He came from around Haik Stiphanos monastery. It was a religious university since twelve century.

I am Ethiopian Franciscan and wish to know more about “Sagga Krstoss”.

I don’t understand what he’s trying to say that African Ethiopians was excepted in Europe before the colonial period but other africans wasn’t an africans was treated like dogs entirely by some European I’m not getting what this article is getting at when me myself is black in America an grew up looking at how terribly cruel an mean white people were to black people I guest he’s trying to put division between people of African decent or trying to say Europe was good to a few African a please forgive my nlyntness but I would love to know the implication of this article Thank u

I meant excuse my bluntness to ur article

This is a facinati.g piece of EThiopian history. At a macro level, Tsega isa facinating personality. The kind of a well groomed, intellgent and magnetic personality that is representative of the elite circle. The kind of personality u would like to spend time with and share long conversations. Can’t wait to get a copy of the book.