Mali: how bad can it get? – A conversation with Isaie Dougnon, Bruce Hall, Baz Lecocq, Gregory Mann and Bruce Whitehouse

Edited by Baz Lecocq and Gregory Mann, from a conversation on 3 April 2012.

From dusk till late evening, you can find small groups of young people sitting on street corners, in front of houses, or in courtyards across West Africa. There will inevitably be a little radio, playing music and broadcasting news. The ‘junior’ of the group is busy brewing and passing round small glasses of tea, while the others hang out, play cards, and discuss the news they hear, whether it comes from Radio France Internationale or sidewalk radio. In Mali, such a group is called a grin. Below, a virtual grin, a group chat among five researchers discussing the news on Mali, from wherever it comes.

The news is bad

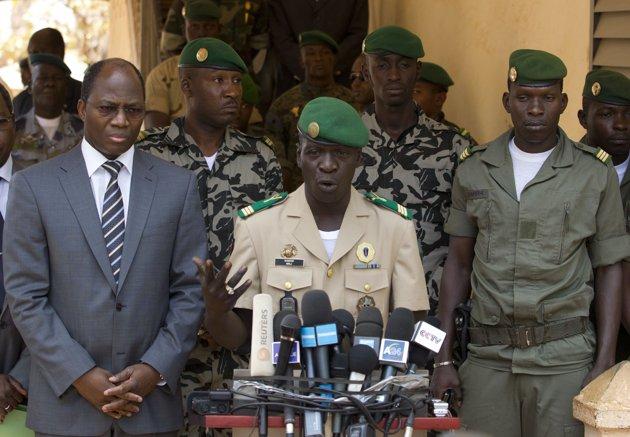

On 22 March, a military putsch chased President Amadou Toumani Touré from power, mere weeks before the end of his final mandate. In the two weeks since, Malian civil society has rejected the junta with near unanimity, while calling for a restoration of the constitutional order. Profiting from the confusion, a rebellion in the Malian Sahara has gained incredible momentum, effectively splitting the country in two. Meanwhile, the international community has roundly condemned the coup, and on Monday ECOWAS imposed harsh sanctions. So where are we now?

Our contributors

Isaie Dougnon (ID) lectures Anthropology and Sociology at the University of Bamako. He is currently a Fulbright scholar at the University of Florida.

Bruce Hall (BH) lectures African history at Duke University.

Baz Lecocq (BL) lectures African history at Gent University.

Gregory Mann (GM) lectures African history at Columbia University.

Bruce Whitehouse (BW) is a Fulbright scholar at the University of Bamako and a member of the Anthropology Department at Lehigh University.

ON THE COUP d’ETAT

GM: Let’s begin with the coup itself””was it planned or spontaneous? “Accidental” or intended?

BW: I keep seeing the term “accidental coup” on the internet, and it seems appropriate to me.

ID: The coup was planned. It was low-ranking soldiers contesting ATT’s management of the conflict in the North and the irresponsibility of the military hierarchy. It wasn’t an accident; since mid-January rumors of a coup have been widespread in Bamako.

GM: But, Isaie, very often, in fact, there have been rumors of coups…

BL: Are rumors and fear of a coup proof that the coup was planned? I agree with Isaie that the coup is the result of these disgruntlements, but is that planning?

GM: I believe it was more improvised than accidental. I think they had thought of it. They might not have known it would be that day, but knew if they were to do it, it had to be soon.

BW: I agree that, in a sense, people could see these events coming… but I don’t believe Captain Sanogo got out of bed on 21 March with the idea of mounting a coup. Here’s why I think it was improvised: the coup plotters’ rationale/justification was incoherent and wide-ranging; it took them over 12 hours after capturing the TV station to broadcast a statement. Their junta name and acronym are so awkward they couldn’t possibly have been planned in advance!

GM: Bruce, you’re right that it was poorly planned, but if we look back at the coup of 1968, there are the same delays and confusion.

DYNAMICS INSIDE THE MILITARY

BH: Why were the military officers unable to contain the so-called mutiny in Kati, or for that matter elsewhere, once the coup had been staged?

ID: Amadou Toumani Touré (ATT) was informed long ago that the garrison at Kati might carry out a coup against him: why did he not take any measures to prevent it? This is the puzzle for me. As soon as he heard about the coup, he called back a group of Red Berets (the Presidential Guard) from the battlefield in order to protect the presidential palace and organize his escape. The Red Berets had only one goal: to protect the bodily integrity of ATT.

BW: I think there’s been a growing gulf between senior officers and the rank-and-file in the Malian military. The former have been associated with politics and corruption, so some of the latter felt they could bypass them altogether in taking this initiative to seize power.

BH: It seems to me that the collapse of the military in the North these last ten days or so is directly related to the officers’ unwillingness to put down the mutiny.

GM: It’s also due to these guys being terrified. Before the coup, RFI broadcast interviews of soldiers who had fled to Niger to avoid fighting!

BH: I mean only to ask the question really, but it seems to me strange that a mutiny could occur in Kati, if indeed it was that, that it would face almost no resistance from the command structure of the military and government, so that there were no loyalist units prepared to confront the mutineers. The same thing seems to have happened in the northern garrisons. In Timbuktu for example, which I have followed most closely, there was no violence in the mutiny and arrest of the military leaders and government leaders in the town.

ID: Sanogo and his group have been sending message to their fellows who were in the North not to fight, because they said ATT was behind the Tuareg rebels. So nobody wants to fight when the president is not supporting them.

BH: The issue of the morale of the troops explains something, but it should not explain the complete collapse of will among the officers. So was this an army rebellion rather than a mutiny of low level troops and officers?

ID: Most of the Malian officers became “civil servants” in different ministries. A huge number of our officers have been fighting to get involved in UN peacekeeping missions in other parts of Africa and the world. Don’t forget about the well-funded UNDP program to train the Malian army to be an army for development and peacekeeping, which ran from 1996 to 2002.

BL: In that case: where are the officers now? Isn’t it too conspiracy-oriented to think they are still there behind the scenes, invisible?

GM: … although it was generally reported that these were low-level officers, in fact a Colonel and a Lt-Colonel are central figures in the junta: Lt.-Col. Konare and Col. Moussa Coulibaly, who is “chef de cabinet,” according to an interview Sanogo gave on RFI this morning.

BW: We didn’t see any senior officers affiliated with the CNRDRE on Television until they read the “new constitution” a few days ago.

BL: The appearance now of senior officers can mean two things: they were behind the scenes all along, or they have recently rallied for unknown reasons so far.

CIVILIAN SUPPORT OR OPPOSITION?

GM: It would appear the junta has managed to expand within the army but has had very little success in acquiring real civilian allies. Thoughts on that anyone?

BW: The SADI political party and its spokesman Oumar Mariko remain the junta’s most visible supporters, plus a few specific newspapers.

GM: Yes, always Mariko, but not a lot of other support from among the politicians, no?

BW: I wonder how much weight Mariko or his party really carry?

GM: To me the guy is a minor figure, although he was apparently behind the airport events on Thursday the 29th, when the ECOWAS delegation was turned back because protestors were on the tarmac.

GM: But Sanogo said later that the junta does not want to be involved with Mariko and SADI, without naming them directly. This is Mariko’s chance to go from minor to major, since among the politicians, hardly anyone else will affiliate with the junta so far.

BH: Given the collapse of the army in the North is there much support left for the coup, or is it now seen as a losing horse to bet on?

BW: I think the CNRDRE and SADI have been trying to paint the current struggle as “Mali vs. foreign powers” or “Mali vs. France,” but most Bamakois I’ve talked to aren’t buying it. Then again, I tend not to hang around with hot-headed young men!

GM: But won’t the embargo give the CNRDRE and Mariko’s message regarding outside interference more traction?

BW: I think that’s a big risk, Greg. But so far the people I’ve talked to just think Sanogo should exit. They perceive him staying on as his putting personal interests above those of the nation.

BH: It seems to me that one of the questions a number of people have raised is the extent to which this coup has popular backing.

BW: Absolutely Bruce, but frustration with the elite doesn’t automatically translate into support for the junta – especially when the latter has made major errors (failure to stop looting or complicity in looting, aggravating international isolation, losing the north…).

GM: Look, what I hear from Bamako and elsewhere is that prices are through the roof and people are anxious, there’s not even much traffic today in Bamako. I think that popular support won’t last and is already fading fast.

BH: I am not arguing that the junta is popular. It certainly is not from the people I have talked to. But it seems that a lot of outside commentators are trying to make this argument.

GM: I think it’s important to separate anti-ATT sentiment from pro-junta support and to place the latter in relation to the timeline of the collapse in the north.

BW: I agree with Greg that junta support seems to be slipping in Bamako, traffic is kind of normal and the market looks full, but it’s mostly vendors rather than shoppers. A lot of people are avoiding the downtown area altogether (and not just expats!).

ID: You know, the junta just wanted to kick out ATT and get somebody else to monitor the fight in North, but as soon as this happened, Mariko and other politicians surrounded the junta to ask it to set up a transitional regime.

GM: Isaie, you are right””and I think that it is interesting that Sanogo suggested he would not accept them. On the other hand, I think Sanogo does not understand the political world he has gotten himself into.

BW: Some people here believe Sanogo is purely apolitical and just wants to find someone suitably apolitical to oversee the transition, that’s the only reason he’s refused to hand over power so soon.

BL: If Sanogo is apolitical and wants to hand over power, why did he have his presidential portrait made so soon?

ID: Sanogo has no clue as to what it is like to lead a country, he is just influenced by many who think that it’s their turn to “eat.”

ECOWAS and THE EMBARGO

GM: Have ECOWAS – and particularly its current president Alassane Dramane Ouattara of the Cote d’Ivoire – pushed too hard and too fast?

BW: All the Bamakois I’ve spoken to say YES. Plus they don’t like the belligerent tone struck by Yayi Boni, President of Benin and Chairperson of the African Union.

BH: I also think that given what happened in Cote d’Ivoire last year, ECOWAS is going to play hardball with this.

BL: I fully agree.

BW: I do too, Bruce. President Ouattara’s experience last year has led him to push for rapid action rather than the gradual approach that stretched the Cote d’Ivoire’s post-elections crisis out into months.

BH: It seems to me this is the most likely way to be effective

ID: If the embargo continues, I am sure in one week Bamako’s population would chase Sanogo from power.

GM: Time is of the essence, then?

BW: Maybe not a week, but definitely less than a month.

THE CRISIS IN THE NORTH

GM: Does Mali even have that kind of time to play with? I wonder if the North can afford that much time in terms of humanitarian intervention and the shipping of food aid. Ouattara is talking military intervention against the junta. Meanwhile, Sanogo is asking for ECOWAS’ help against the Tuareg rebels of the MNLA, et al. Thoughts on this?

ID: Mali cannot get any help as long as Sanogo hangs on to power.

BW: I think Malians would welcome ECOWAS’ help in taking on the MNLA. But let’s be honest, the last thing Mali needs right now is thousands of ECOWAS soldiers with automatic weapons running loose on its territory.

BH: It’s already over in the north. There is nothing to do until a proper administration is in charge in Bamako. And then, it will be a tough job getting back up there.

BW: I don’t think the “international community” will accept a partition of Mali, especially not if Islamists are involved

BH: They may not accept it, but as we have seen in Somalia, they may have to live with it…

GM: Would the best way out, then, be for whoever is in power in Bamako to give MNLA a lot of what it wants in exchange for its opposition to Ansar Dine, et al.?

ID: The problem is not MNLA, it’s Ansar Dine and other terrorist groups.

BL: But even that won’t mean it’s over – I just read that the World Food Program and other big NGOs are pulling out of the North.

GM: Look, a low level insurgency in the North is one thing – outside the cities this has been going on for years, as you know – but the entire North as a “no-go area” is another question. The UN World Food Programme is pulling back at a very difficult moment. But what can they do? The MNLA is going to be responsible for a humanitarian disaster that their media wing will have a hard time covering up.

BW: Baz, do you think there’s a way for the Tuareg population to accept anything less than full territorial sovereignty of the “Azawad”?

BL: Yes. I don’t think support for the MNLA is very high, not en brousse, while Ansar Dine and others are very unpopular with locals.

BW: Can you give us an idea of who the MNLA’s supporters are?

BL: They are city-based Tuareg, mostly from the Kidal region and part of the Gao region. I suspect many Tuareg from around Timbuktu have turned over too after the sackings of Tuareg homes and businesses in Kati.

BW: Baz, does the MNLA’s urban base explain the fact that they weren’t able to hold on to Timbuktu?

BL: Were they not? Was their withdrawal forced as is claimed?

BW: The Ansar Dine drove them out!

BH: The MNLA were not driven out of Timbuktu from what I hear from people there. Just that there were only ten or so 4x4s of the MNLA in the first place, and that they left the next day after “taking” the city. This is when Iyad ag Ghali, the leader of the Ansar Dine, came to Timbuktu.

GM: You know the North – no one knows for sure what’s what. But I heard the same thing directly from Gao – that the MNLA had withdrawn, that the Ansar Dine remained.

BL: My take is that the MNLA is not trying to hold the cities for the moment. They are interested in the strategic positions to hold the North against the Army. So they leave Ansar and company a free hand to “play sharia,” which is a bad move as it gives them bad press.

ON THE MNLA AND THE ANSAR DINE…

GM: So how long can the MNLA / Ansar Dine alliance last?

BL: Is there an MNLA / Ansar Dine alliance? Or are they just coordinating attacks as long as their goals are common?

BW: What strategic interest does the MNLA have in allying with Ansar Dine? Don’t they realize this is the kiss of death in terms of their image abroad?

BL: They do realize that and deny all alliance formally.

GM: Yes, they swear up and down that there is no alliance… My take is that the MNLA is trying to disentangle itself from the Ansar Dine, but failing to do so. You are right. This is a disaster for their public image. But who is playing whom?

BW: Maybe the “alliance” exists more in the Bamako papers than in reality?

BL: I am afraid so. Read articles carefully – most analysis of the North is based on people in the South, plus some phone calls.

GM: Hold on, these look like clear joint actions between the MNLA and Ansar Dine, which the MNLA denies for political reasons, while Ansar Dine remains mute. The question is when will it break down, will it be sooner or later?

BH: The one lesson of Northern Malian history is that unity is unlikely to hold.

CIVIL WAR IN THE NORTH and MILITIAS

ID: I fear a civil war in Mali’s North.

BW: Isaie, when you say you fear a civil war in the north, do you mean the central government against the Tuareg rebels, or the MNLA vs. Ansar Dine, or some other combination?

ID: By civil war, I mean war between different Northern ethnic groups.

BH: Civil war in the North is very likely.

GM: Can we talk about the militias, “Arab” and others?

BL: Isaie you’re right, we have not seen or heard the last of the Ganda Koy and Gando Izo militias.

GM: The junta has started to arm militias””some were killed last week in fighting.

ID: The munitions from the Gao army base have been distributed to the civilian population.

BL: Bruce, didn’t that also happen in Timbuktu?

BH: The army was arming militias in Timbuktu since January and giving them training – calling them neighborhood brigades. Also the Timbuktu Arab militias have had government support, arms and training for a number of years now. The collapse of the army in the North led to looting of arms in the military camps. I think it is a safe bet that this is far closer to the beginning of this story in the North than the end… If you want to know what is going to happen in the North, listen to all the MNLA spokespeople who insist that they want an Azawad for the blacks and whites. They constantly use this language of race but I think they doth protest too much. The North is in a mess that it will not get out of easily or soon.

BW: Does anyone think the fighting will extend further south than it already has?

BL: No, there will be no fighting in the South. The MNLA won’t risk it, and Ansar Dine is too small.

GM: On the other hand, whether or not the MNLA or Ansar Dine push on South, what is likely to happen is extreme insecurity, banditry, etc., throughout the country. This will be hard to attribute to any political group.

ID: I think MNLA does not weigh in the current situation; it has a very good communication strategy, but no military force.

BH: MNLA spokespeople keep bringing this up unprompted. I think it points to what they know is really the central problem that cannot be resolved even by taking the territory. There is no Tuareg homeland.

GM: Baz, do you agree that there is “no Tuareg homeland?”

BL: There was no Mali in 1960 either, or most other national states in Africa for that matter. Homelands are in the mind and can become real or not. The problem is the Niger River and the Inner Delta; there are many Tuareg living there. Many don’t mind at all being Malian.

BH: But since the 1950s, the problem of borders and shared territory has rendered a geographic homeland impossible.

INTERVENTION, THE MNLA, PREDICTIONS

GM: Is there a productive role for other outsiders to play””the UN, France, the USA?

BH: Ending the coup is the single most productive thing outsiders can do, in my view.

BL: France is ambiguous. Its press over the last few days is too eager to stress the Islamist story over all others. Is this preparation for an intervention?

ID: France was always ambiguous as far as Mali is concerned.

BW: France has already ruled out intervention. But it’s hard for me to see France playing a productive role, if only because so many Malians see it as the incarnation of all evil for some reason. The USA has a better reputation in Bamako, but I can’t see any involvement in an election year.

GM: France will act like it owns the dossier in the UN, etc., as if it were a responsible party rather than a reckless actor (as in Libya)…

ID: I am not against the military intervention against the junta, it’s the only way to speed the humanitarian aid and to begin negotiation with the rebels.

BW: Isaie, you’d welcome thousands of foreign soldiers on Malian soil?

GM: I tend to think that an ECOWAS military intervention – boots on ground – would be a disaster in all respects.

BW: Me, too.

ID: It’s more and more clear even for France, the MNLA’s European Union ally, that the radical Islamists are more powerful than the MNLA.

BL: Isaie, that is simply not known. No one knows the real strength of either movement.

GM: Yes, Baz, but it is widely believed that the MNLA has enjoyed French support.

ID: France seems to be in an MNLA trap, since they promise to liberate the French hostages from AQMI.

BL: Greg, yes, that’s true, but, Isaie, no one knows who is the stronger party in the North, no one knows why the MNLA retreated, if it did. No one knows much because there’s no communication…

LIBYA AND NIGER

BW: Can we discuss the Libya angle? Many journalists and some political actors in Bamako are describing Mali’s current crisis as a more-or-less direct effect of NATO’s bombing campaign. How do you all feel about this question?

GM: Yes, the argument that NATO saved Benghazi to lose Timbuktu…

BL: I still think the connection between the Tuareg uprising and the Libyan arms they brought does in fact exist, but was not a cause or decisive factor in the rebellion. If the Tuareg want arms they can get them anyway, they have proven that before. The MNA, the MNLA’s political wing, existed before the Libyan crisis broke out and the ATNMC, one of the MNLA’s main military wings, dates from the 2006 rebellion. Everything was in place except a bunch of arms.

GM: But Baz, was the return of Ibrahim Bahanga and Mohamed ag Najim and his fighters not a decisive factor in battles in the North that soured the army on ATT?

BH: The Libyan campaign did lead to this directly, even if it did not provide the motivation or create the history and imagination of what might be accomplished.

BL: I agree, but if “Libya” had not happened, the current uprising might still have happened with weapons coming from elsewhere.

GM: So was the Libyan campaign “a cause or decisive factor”?

BH: I think the bombardment of Libya was absolutely decisive in the timing of this, in the access to weapons and organization of many people forcibly returning to Mali at the same time. However, absent the Libyan campaign, such a conflict in northern Mali was always likely at some point or another.

BL: It was a trigger, but a circumstantial one.

ID: Regarding Libya, there are three further factors to consider: first, the subordination of Mali’s policies to Qaddafi since the time of Alpha Oumar Konare from 1992 to 2002; second, the role of Qaddafi in security issues in the Sahel,; and third, the war in Libya and the return from there of thousands of heavily armed soldiers.

BL: But many of those returnees wanted to join Mali’s army, not fight it!

BW: Didn’t Nigerien Tuareg also go to Libya? If so, why didn’t they come home and destabilize Niger?

BL: Exactly! They had no motivation to do so, and the history of state-Tuareg relations in Niger is very different from that in Mali.

GM: It appears that Nigerien President Mahamadou Issoufou has a tight lid on the North of his country, and he seems to have a big investment project at work there.

ID: There is a big difference between Niger and Mali: ATT let the armed ex-Qaddafi fighters enter Mali. This is a puzzle.

BH: It is important also for those not so versed in Sahelian affairs, that the Libyan conflict has had wide repercussions that were unintended if not entirely unpredictable.

GM: Even effects that were really very predicable!

WRAP-UP

GM: Let’s wrap up: Where are we now?

ID: I am asking myself whether ATT has any idea of what it means to secure a country. Since 2005, the current MNLA fighters were allowed to leave Mali with arms and munitions, go and store them in the Iforas Mountains, and return to Mali’s army. They did this coming and going until 2010. Having acquired enough arms, they declared war on Mali. This means they bite the hands that fed them.

BL: Realpolitik: keep international pressure on Sanogo, support the MNLA in its struggle with Ansar – a struggle that will be coming anyway – settle for negotiations with some real change for the North regarding administration and real infrastructure investments, get peace soon and help victims of drought before mid-May.

BW: I don’t see any promising ways forward. The central government needs outside help to combat the rebellion, but we can agree that an ECOWAS military intervention would bring all sorts of unwelcome consequences, even if it managed to temporarily address the security issue.

BH: My fear is that it is very hard to put together a state that has collapsed like this. I remember the years of banditry outside Timbuktu after the rebellion [of the 1990s], just because this had become a viable living for some in the disorder of the conflict. I suspect that there are going to be many long years ahead for Northern Mali. I hope the rest of the country will not go down the same hole. I also think we need to remember that some people benefit from the political economy of war. In the north, there are quite of few interests lined up against peace. And there is going to be a very large humanitarian crisis in the North very soon.

GM: I agree, Bruce. It will be a long road back””for the North, for all of Mali, but also for the idea of representative and inclusive government.

ID: The way forward: there is no military solution to this war, as Mali has no army to fight with. So ECOWAS has to mobilize the UN, and the US to disarm the armed groups and restore Mali’s territorial integrity.

For more analysis on the current situation in Mali click here

Sanago was trying to defend his country from jihad. He asked ATT for more arms, as the Mali army was outgunned. ATT didn’t help, so in desperation Sanogo took over. He needs help and aid to defeat jihad, not sanctions and embargo. ECOWAS and the West are doing exactly the wrong things: punishing and starving the civilians, almost as if they want to invite the jihad to take over.

Merci messieurs, always profitable to hear your views. Particularly helpful (if not encouraging) are your questions about the MNLA — Ansar Dine relationships, and the challenges of territorial integrity faced with armed alternative visions of imagined community.

Thanks, John and Fred.

Fred, the rebellion in the North is a lot more complicated than a jihad, as we tried to make clear. And ECOWAS’ sanctions are meant to be a sharp shock. We’ll see how long they last.