“Warning shots”: The steady rise of political violence in Ghana

A combination of mistrust, concerns around fairness of the upcoming 7 December vote, and inequality have contributed to a rise in violence.

Citizens celebrating after a peaceful presidential election in 2008. Credit: Naeema Campbell.

On 20 July 2020, residents of Kasoa, on the outskirts of the capital Accra, were registering to vote in the upcoming elections when gunshots forced them to take cover. The frightened citizens assumed the shots had been fired by a criminal gang or vigilantes, but it soon emerged that the person responsible was a Hawa Komsoon, the local member of parliament. The politician later claimed that she’d fired the “warning shots” in order to “protect herself”.

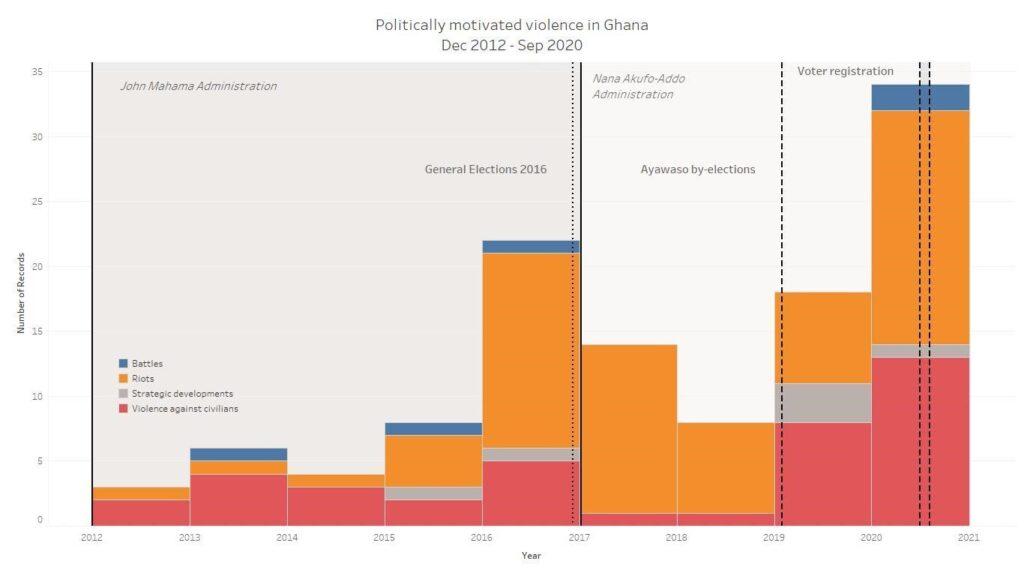

This particularly incident may have been unusual, but political violence in general has become far less unusual in Ghana recently. An official of the National Peace Council recently stated that 86 constituencies experienced violence around the 2016 elections, compared to just 47 in 2012. ACLED data suggests the frequency of politically-motivated violence spiked in 2016 and has remained high ever since. And popular attitudes in Ghana have grown more wary, with 43.3% of respondents in a 2018 Afrobarometer survey saying they feared becoming victims of political violence, up from 35.5% in 2014.

Politically-motivated violence in Ghana (2012-2020) committed by political militias, party supporters and unidentified gunmen against civilians. Credit: ACLED.

With general elections scheduled for 7 December 2020, election-related violence has been rising again. The climax of this so far was during the 31-day voter registration process this summer when supporters of the ruling New Patriotic Party (NPP) and opposition National Democratic Convention (NDC) clashed in several constituencies, leading to multiple fatalities.

How violence becomes an answer

A number of factors have contributed to this trend. In Ghana, as in many countries, the rule of law is often applied selectively. In particular, elites are more likely to get away with crimes, even those committed in full view. This includes the MP who fired a gun in public this July, or another politician who called a judge “stupid” and threatened him this September.

Moreover, when the police do intervene, they often fail to bring criminals to justice. Investigations are frequently left incomplete, leading to speculation that the suspects bribed the police or were let off the hook because a powerful figure influenced the process. The lack of repercussions for such public offences erodes trust in the rule of law and contributes to an environment in which citizens feel emboldened to take the law into their own hands too.

In the lead up to the 2020 elections, this broader environment has combined with specific disputes. In particular, there have been growing tensions around the freeness and fairness of the upcoming poll. John Mahama, the former president and opposition NDC candidate, has accused the Electoral Commission of bias and threatened to reject the results. He has claimed that the ruling NPP and President Nana Akufo-Addo have installed an ally in Jean Mensa as chair of the commission. For its part, electoral officials have done relatively little to bring all parties on board and assuage concerns.

These rising tensions came to a head around the voter registration process, which has been a previous flashpoint for disagreements in Ghanaian elections. On this occasion, the NDC accused the Electoral Commission and NPP of attempting to disenfranchise its supporters by deciding to accept only passports or National ID cards as proof of citizenship. These disputes filtered down to the street level where opposing party supporters clashed during the registration process. Many voters, particularly those sympathetic to the NDC, have little confidence in the electoral process, feeding notions that the people themselves – including through party-affiliated militias – must mobilise to ensure the legitimacy of the vote.

Underpinning this political violence, however, there are even deeper dynamics. Despite economic growth, poverty remains high and inequality becoming more stark and visible in Ghana. For instance, this government includes 123 ministers. The taxpayer-funded affluent lifestyles enjoyed by these senior politicians contrasts heavily with those of their constituents, many of whom struggle to access potable water, decent roads and jobs. These widening inequalities have increased tensions, mistrust and political frustrations. On several occasions, MPs’ visits to certain areas have been met with protests over poor infrastructure and unmet promises. Recently, a separatist movement in Ghana’s Volta region ransacked a police station, burnt tyres and blocked major roads. It appears their activities were borne out of perceptions of the government’s neglect of the area.

Tackling the roots of violence

The administration of President Akufo-Addo has taken some action in response to rising political violence. In September 2019, it passed the Vigilantism and Related Offences Act, which criminalises vigilantism, disbands vigilante groups, and promises up to 15 years in prison for anyone “who directly or indirectly instigates or solicits the activity of a vigilante”.

This may help authorities clamp down on certain groups and certain acts, but until the deeper roots of people’s frustrations are addressed, it will be difficult to meaningfully reduce political violence. At the moment in Ghana, political violence is being committed by a broad range of actors and in a variety of ways, from riots to more targeted attacks against civilians.

Whoever wins Ghana’s 7 December general elections, this will be a key challenge over the coming term. Unfortunately, it is one that could be made even more difficult by the poll itself given the relatively low levels of trust in the process and the likelihood the result will be disputed.

Stop the misinformation you are putting out there.

Since 1992 when it’s come to political violence NDC is the perpetrator,it seems Ghanaian reporter’s doesn’t want to talk or write when NDC is the culprit. The atrocity NDC has committed on their opponent’s, its sad no newspaper has published them. God have Mercy on you journalists in mother Ghana.

You were spot on .

The winner takes all politics is takibg Ghana to the bottom

it is pathetic that our country ghana should be experiencing these violence. Ghana started marvelously but this mischivious politics of tribalism and sectionalism have brought us to this end. The level of literacy in the country too is nothing to write home about. We cannot however, throw our hands in the air. We got to combat this sooner or later.