Debating Ideas is a new section that aims to reflect the values and editorial ethos of the African Arguments book series, publishing engaged, often radical, scholarship, original and activist writing from within the African continent and beyond. It will offer debates and engagements, contexts and controversies, and reviews and responses flowing from the African Arguments books.

There have recently been violent attacks on African students in India. Yet public stories about such events and African-Indian relations more broadly are often stark and simplistic. They tend to be written either as an illustration of the enduring power of global anti-black racism or an example par-excellence of post-colonial, South-South co-operation. In the interview below, Shobana Shankar and John Patrick Omegere go past these narrative tropes to explore the complexities and importance of African student experiences in India, and relations between the two regions more broadly.

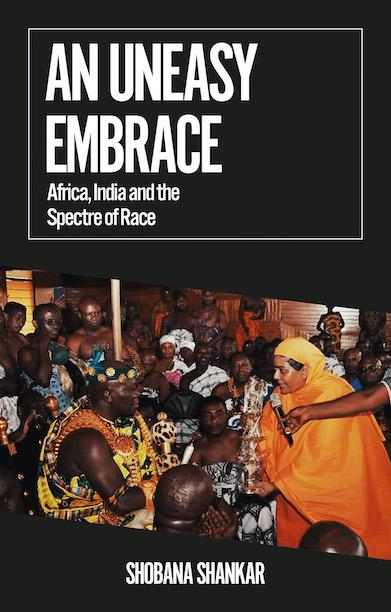

Their conversation unfolds across a unique connection. Shobana is an Indian-American by birth, who studied in Nigeria during her university days, while Patrick, a Ugandan, studied and worked in India. They met through the University of Mumbai African Studies Centre, where they discovered their mutual interests. Patrick is a past President of the Association of African Studies in India (AASI) and holds two degrees from universities in Pune, and currently works for the Global Development Centre (GDC) at the Research and Information Systems for Developing Countries (RIS) in New Delhi. Shobana is a historian, whose forthcoming book, An Uneasy Embrace: Africa, India and the Spectre of Race, is being published in the African Arguments series in July 2021.

Patrick Omegere who works at the Global Development Centre of the Research and Information Systems for Development Countries (RIS), New Delhi. He earned scholarships from the Indian Council for Cultural Relations and Symbiosis University. He has been an intern at Observer Research Foundation, one of India’s most prominent think tanks, and Talking Across Generations fellow at UNESCO/Mahatma Gandhi Institute of Education for Peace and Sustainable Development.

This discussion provides a much-needed perspective on the world of African students in India – a complex world that has been shaped and reshaped by simplistic narratives. In this discussion, Patrick and Shobana both kept returning to the word ‘unease’. What is this unease? Is it between Africans and Indians? Or is it a generational problem between young and old? Or is it between civil society actors and their governments?

Shobana Shankar (SS): Perspectives of young Africans in India have not been covered in usual narratives—there is development, on the one hand, which is not really spelled out in concrete terms, or, on the other side, there are negative incidents of racism and discrimination against Africans in India. And the youth have perspectives on both—we need to cover these angles. You are young, professional, upwardly mobile in aspiration—how do you see things?

John Patrick Omegere (JPO): I agree with you, I think a lot more needs to be done to bring perspectives of young Africans (in India and in Africa) into the discourse on Africa-India relations. Like you mention, most times such engagements happen only when ugly incidences happen, and even these are mostly covered in media reports. I think this risks leaving young people behind and consequently, preventing appreciation of the historical and present significance of India-Africa relations. But there are some steps: RIS — where I work — has ‘a young scholar’s program’ that draws active participation by youths from Africa, and as you are aware, the Centre for African Studies at the University of Mumbai runs an internship program also targeting African students in India. These are steps in the right direction. But I still think there is need for a more concerted effort particularly aimed at engaging young Africans living in India. As you know, ‘diaspora’ and ‘capacity building’ are major words in India-Africa relations. African youth in India tick these two boxes. I think their engagement would bring unique viewpoints that enrich the study of India-Africa relations…

SS: Tell me about yourself. Your trajectory to India, when you went, how long you stayed. Do you call yourself an immigrant to India? Or just passing through?

JPO: I went to India in June 2014, and that was as a result of an African scholarship scheme offered by the Indian Council for Cultural relations through which I studied commerce at Pune University. I later enrolled for the MA in International Studies at Symbiosis International University, which I completed in May 2019. I have been associated with Research and information Systems (RIS) for developing countries, since June 2019. Even after I returned to Uganda in October 2019, I still work (virtually due to Covid) for one of the Centres at RIS called the Global Development Centre (GDC). In total, I lived in India for close to 6 years during which I spent time in Pune, Mumbai, and New Delhi. Even now as I am in Uganda, I feel very attached to India. I cannot really call myself an immigrant to India, rather I passed through.

SS: What is your view of the relationship between African countries and India? Is it interdependency? Is one more powerful?

JPO: The expressions from the Indian and African governments (but not so much of the masses) allude to the view that both India and Africa need one another. It is important that this view is upheld. Just like Indian entrepreneurs would find Africa’s 1.4 billion consumers an interesting market, many African enterprises are very keen on penetrating the Indian market. India is an important export destination for goods from Africa, and exports from Africa are vital for India’s energy security (for example). The other critical aspect is support in multilateral forums (which I think is increasingly important), be it the UN (especially the crucial seats at the UN Security Council where each party is currently holding one semi-permanent seat), G20, or WTO, among others. India leads initiatives like the International Solar Alliance (ISA) and Coalition for Disaster Resilient Infrastructure (CDRI). In all these multilateral engagements, India-Africa cooperation can be mutually beneficial. Commonality of concerns raised by India and Africa should be a strong basis for cooperation. It is important that we continuously highlight the mutuality of India-Africa relations. Consider capacity building programs. While African students benefit from scholarship offers, Indian students also benefit from the increased diversity in the classroom – which I think is an invaluable contribution to the development of Indian students.

SS: What does Afro-Asian solidarity mean? That is an older politics, but how relevant is it today?

JPO: There may be instances of an uneasy embrace between Africans and Indians. Social, cultural differences, and sometimes lack of knowledge, have particularly been barriers for people-to-people relations. This is really why I think enhancement of people-to-people engagement should remain at the core of India Africa relations. In this regard, diaspora engagement —particularly African students in India — is important. The Indian government has listened to concerns raised by African students. I very vividly remember many instances where I met senior government officials, and they genuinely listened to our concerns – that was very important. However, sometimes substantive action takes a lot of time. I can understand that as part of the long bureaucratic procedures involved with all government actions; however, if such student welfare concerns are addressed decisively, it would go a long way in improving the student experiences in India. Many Indians have numerous misconceptions about Africa and Africans, perpetuated by biased media reports. A lot needs to be done to sensitize the local population about Africa. This must be a combined effort by the African missions in Delhi and the government of India. In my experience and that of many students I interacted with, African students in India encounter innumerable challenges while in India: accommodation, cultural shocks, documentation process, finances, among others. Imagine, an 18-year-old moving to such a new environment, far away from parents, and having to figure out everything – food, shelter, academics, etc. – on their own. You would agree with me that not so many can manage that, and if they did, they would get overwhelmed, it is stressful, there could be errors in judgment. My view is that when such errors occur, they should not be read as deliberate mistakes, rather errors that any adolescent could commit, and he or she just needs to be called out for it. Unfortunately, this has not been the case because of existing notions about Africans. Consequently, many Africans are immediately found guilty of acting in manners deemed unacceptable, and without any legal process, corrective measures are enforced, very often violent. Violent attacks against African (students) in India must be condemned and decisively dealt with.

The experiences of African students in India vary according to gender. As you know, India and Africa have a long road ahead in terms of attaining gender sensitive communities. Female students speak about teasing, unsolicited sexual comments, and other forms of harassment based on gender. In this regard, female students have to be more careful.

India-Africa solidarity was crucial for Africa’s independence struggle. Whereas political independence is very important, it is not sufficient. Youth yearn for more. It is worth mentioning that some even question if they have political independence especially because former colonial powers and other global powers still wield high political and economic influence in the continent, and global institutions are not reflective of this independence. But assuming we have political independence, young people in Africa are now thirsty for economic independence, and desire ultra-modern lifestyles. And just like our parents struggled for political independence, the struggle for economic independence is extremely important. I think India-Africa solidarity is of immense potential in this regard. Innovative development experiences from India may be important in catalyzing development processes in Africa.

SS: I would like to know more about the relationships between African students and their Indian colleagues and friends. How do they relate to each other? Do they date?

JPO: Relations between African students and the host Indians is very complex maybe reflecting the complexity of the Indian community itself. It seemed that higher levels of exposure, religious commonalities, shared minority feeling, region of origin (Indians from the North East and Southern states) could make some Indians seem friendlier to Africans. I think the existing internal dynamics amongst Indians influences the level of ‘interaction’ with Africans.

There are instances of male African students dating Indian girls, but very few of the opposite. Some of these relationships have resulted in marriage.

SS: How important has the Association of African Students in India been in the lives of African students like yourself?

JPO: Since former Malawian President Hastings Banda founded AASI in 1961, it has played a pivotal role in the life of African students in India. Even before beginning the admission process, many students write to AASI seeking guidance. When they get to India, AASI is that comfortable space where students gather and support one another, in innumerable ways. Social and sports activities are vital in this regard. AASI also engages private enterprises for internship opportunities for African students, in addition to arranging capacity building activities — seminars, workshops and trainings. Under AASI, students also gather to collectively reflect on major issues in Africa, which I think is vital for effecting change in Africa. In all, AASI plays a vital role in the life of African students living in India from the preadmission process to the time when they leave. I would therefore like to underscore the importance of supporting AASI activities. When I was president, I would get support from the Indian Council of Cultural Relations, but that was occasional. I also had a very good working relationship with different government institutions especially the police commissioner. AASI should continue these engagements.

SS: There’s a Hindi language aspect. If you don’t speak Hindi, you become very foreign.

JPO: India is a diverse country, and other minority groups end up in a situation similar to that of African students — for example those who don’t speak Hindi. In fact, these groups could show more support to African students.

SS: Do African students in India think of themselves as one? As Black? The Nigerian writer Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie has said that she became Black in the United States, though in Nigeria she identified as Igbo. Is there a similar experience with African students in India or other lands to the east?

JPO: Broadly, African students in India identify themselves as ‘African’. But within the African community, there is a tendency to split into smaller identities, let’s say West Africans, East Africans, North Africans etc., and even nationalities, for example ‘Nigerians’, especially as the Nigerian community in India is very large. But these divisions are mostly within the ‘African’ community. Outside this community, the African identity — sometimes wrongly referred to as ‘Black’ — overrides smaller divisions.

SS: In India we have the same regionalism. What do Africans in India think about the caste issue?

JPO: Many African students do not appreciate strict adherence to the caste system. Personally, I was more interested in understanding the schemes set up to address the injustices that may have been perpetuated by this system. I think India has done well in preserving some good traditional practices and hope they keep discarding whatever is considered unfit. Most of my friends, even from upper castes, did not seem to regard it highly. Some of them would tell me that if not for parents, they would not necessarily marry (for example) from the same caste. I hope it will be a matter of lesser importance, over time. Many of my Indian friends did not seem to agree with the caste division. Therefore, I think it mostly generational baggage.

SS: What about the generational divides in Africa as young Africans see them?

JPO: In many aspects, most of the ‘old guards’ — you know their name — tend to focus on maintaining their grip on power, sometimes with support from some external powers (funding agencies and direct foreign government influence) — and, you know, these days the world is very polarized. It is increasingly unlikely that even the civil society organizations, media, etc., would accurately carry the voices of ordinary people. I am so afraid that authentic Ugandan voices are getting muffled and their thinking is subtly but surely shaped by such media and CSO influences. In these regimes, high defense budgets, corruption, and indebtedness to external actors, are prevalent. And as you could imagine, these would not enable Africans to earn their hard sought economic freedom. For young people, this is an attack on their present and future. This explains the recent spates of youth-led protest — capitalizing on social media — around the continent. South-South cooperation holds promise for economic independence for young Africa, and India can play a vital role in this regard.

SS: Do you think young Africans and Indians see current challenges facing their countries in the same ways?

JPO: I think there are similarities and differences. For example, inequality (incomes, opportunity, gender etc.) is a major concern common among youths in India and Africa. However, inequality for Indians seems to have been perpetuated by social structure especially caste. However, for many African countries, it appears to me that inequality is on the basis of which tribe has ruled longer. Castes and tribes may seem different, however, both revolve around political power, though for India it is an ancient historical power system, while for Africa it seems more of a recent power distribution.

SS: Your point is well-taken, in both African countries and India, political power needs to be less centralized in a few hands. And with young populations so large on the continent and the subcontinent, their perspectives on politics should get more attention. Thank you, Patrick, for sharing your experiences and views.