Nigeria: The cautionary tale of the fateful 2020 strike that never was

Just days before #EndSARS, Nigeria’s labour congress disappointed many by calling off what had promised to be a similarly momentous protest.

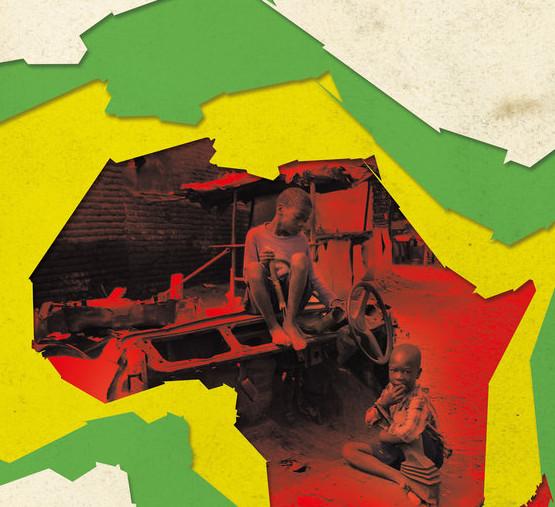

Outside the NLC headquarters in Enugu, Nigeria. Credit: Immaculata Abba.

On the morning of 28 September 2020, John*, a member of Alliance on Surviving Covid-19 and Beyond (ASCAB), woke up and prepared to head to Unity Fountain Park in Abuja. He got himself ready to distribute flyers and placards at the protests in support of what was set to be a momentous nationwide strike.

At the start of that month, the Nigerian government had prompted dismay when it announced a fuel price increase from N148/litre to N162/litre and a doubling of electricity tariffs. This would have been hard to stomach at the best of times, but nine months into the Covid-19 pandemic, workers – many of whom had lost their jobs or seen their salaries slashed – were outraged.

The Central Working Committee of the Nigeria Labour Congress (NLC) had quickly gathered and, on 16 September, published a communiqué. It called on the government to reverse its price hikes and “demonstrate its commitment to resuscitating Nigeria’s four public refineries and building new ones”. If these demands were not met within two weeks, the declaration warned, “the NLC will begin a mass mobilization of the Nigerian people, professional groups, religious organisations, market women, the informal sector and allies in civil societies towards total compliance to the indefinite strike action”.

This was no empty threat. In the following days, all the unions registered under the NLC and Trade Union Congress (TUC), as well as affiliated civil society organisations, made preparations to join the action. Countless workers across Nigeria went to bed the day before the strike ready to take to the streets the following day.

Yet, at 3am on the morning of strike, the NLC and TUC suddenly called it off. Many union members and supporters were deeply disappointed. “We had real hope,” says John. “Unlike other strikes which get cancelled two, three days before, this one came very close.”

That same morning in Lagos, Comrade Omole found himself similarly devastated. The trade union researcher and member of the Socialist Party of Nigeria had also been preparing for the strike. On hearing rumours that the strike had been called off, he boarded a bus with other would-be strikers and headed to the NLC building.

“Close to a hundred people were in the hall waiting to challenge the union leaders on how they called off the strike,” he recalls. “People were angry and disappointed. The union leaders had to come with bodyguards.”

The crowd was told that the strike was cancelled because the government had promised to reform fuel subsidies and provide workers with a financial support package. Few of them were convinced. Later that day in Abuja, civil society leaders staged a protest in the NLC compound. Nearly a year and a half later, the cancelled September 2020 strike is still seen by some as a cautionary tale about the limits of organised labour action in Nigeria.

“We need the older people’s structures”

The labour movement has long been active and influential in Nigeria. Since 2000, unions have successfully called eight general strikes – for comparison, the UK’s last general strike was in 1926 – some of which have resulted in significant victories. In 2012, for instance, a nationwide strike along with huge protests forced the government to rescind its removal of fuel subsidy.

There is good reason that so much of Nigerians’ discontent is directed through union action.

“The NLC and the TUC are very efficient in mobilisation,” says Jack, an organising member of the Socialist Labour movement. “They have a framework across the whole country. They can call a strike down to the smallest village in every local government.”

“The unions are the ones that have the structures in place,” adds Omole. “They command all economic tiers in the country. While we need the anger of younger people, we need the older people’s structures and structural power.”

Even many Nigerians who are most inconvenienced by the strikes have some faith in the nation’s labour movement. For instance, Fumnanya, a graduate of the University of Benin, had her education repeatedly disrupted by strikes called by the Academic Staff Union of Universities (ASUU) and Non-Academic Staff Union (NASUU), but came to recognise the necessity of these bodies and actions.

“Their strikes actually bring results, though not every time,” she says. “Initially, I hated them so much because as a student it felt like elephants are fighting and I am the grass suffering, but in reality there is only one elephant. Federal university academic and non-academic staff are grass like me.”

In the coming years, Nigeria’s labour movement may become even more relevant. The perennial question of the fuel subsidy remains a live issue, with the president suspending the plan for subsidy removal again last month. The exchange rate is falling and the cost of living rising. Agitation continues to bubble from all corners of the country.

However, while most people recognise the power of Nigeria’s unions, not everyone supports their approach. In the wake of the cancelled September 2020 strike, NLC president Ayuba Wabba explained the reasoning behind its last-minute change of heart. “The purpose of every trade union is to try to see how issues can be resolved through collective bargaining and well-tested process of negotiation,” he said on Channels TV. “What we have achieved is that those issues have been put on the table”.

For many union members, putting issues on the table – ones that have been on the table for 30 years as Wabba himself admitted in the interview – is far from enough. They want to see an alternative model of intervention.

“Antagonist to the Left”

Interestingly, Nigeria saw what that alternative could look like just ten days after the September 2020 strike was called off. On 3 October, a video was posted to Twitter showing a Nigerian police officer shooting a young man. The clip went viral and, in the following days, thousands of people across Nigeria took to the streets as part of the #EndSARS protests. This movement grew exponentially. Though it began by calling for the abolition of the notoriously abusive SARS police unit, it quickly spiralled into much broader political demands. In many ways, these protests were the inverse of typical union strikes in that they were largely spontaneous, non-hierarchical, youth-led, and uncompromising.

A few days into the movement, the NLC senior management issued an internal memo disavowing any association with #EndSARS. Nonetheless, many union members joined the protests enthusiastically. In Cross River and Adamawa states, NLC headquarters were among the buildings vandalised in the protests.

According to Jack from the Socialist Labour movement, the position of the NLC and other establishment unions towards the decentralised movement was unsurprising. “Labour fights the government, yes, but it is even more antagonistic to the Left and to anarchy,” he says. “What it wants, above all, is really conciliation, at whatever cost.”

“Planning for the alternatives”

Nearly a year and a half since those eventful months, memories of both September’s stillborn strike and October’s #EndSARS tumult live on.

For some union members, the labour movement has continued to disappoint as it has planned and cancelled further actions. In December 2021, for instance, the NLC announced plans for a general strike in January 2022 in response to the government’s decision to remove the fuel subsidy, a move that could see prices nearly double. A recently published PUNCH article quotes a security officer saying that “the protests being planned by unions would have been 10 times bigger than the #EndSARS protests”. Yet once again, the strike was called off.

According to Omole, the organisers don’t seem to grasp the frustration these events cause among ordinary members.

“For the strike the NLC was organising last month, they called a meeting with [civil society] leaders to rally our support. When I made the frank point that September 28, 2020 remains a betrayal for us, the NLC leaders went on the defensive, saying we don’t understand how strike works,” he says.

For members like Omole, it is important to remember these disappointments and to explore alternative avenues of protest. For all the labour movement’s networks and power, many workers feel they cannot trust their unions’ management and emphasis on conciliation. While remaining part of unions, they are increasingly looking to other routes to express their discontent too in ways that could end up reshaping the landscape of popular movements in Nigeria.

“What made it easier to get over the disappointment of the September strike cancellation was that we were already agitating over police brutality on social media and planning a democracy protest on Independence Day [1 October],” recalls Omole. “As we left the NLC that day, we just poured all that anger and frustration into mobilising and planning for the alternatives. Yes, we had hope, but we also had alternatives.”

*name changed

This article is published as part of the African Arguments fellowship for young freelance journalists.