The case for removing US sanctions on Sudan

Suspending or re-imposing sanctions could not only discourage any future progress, but also jeopardise that which has already been made.

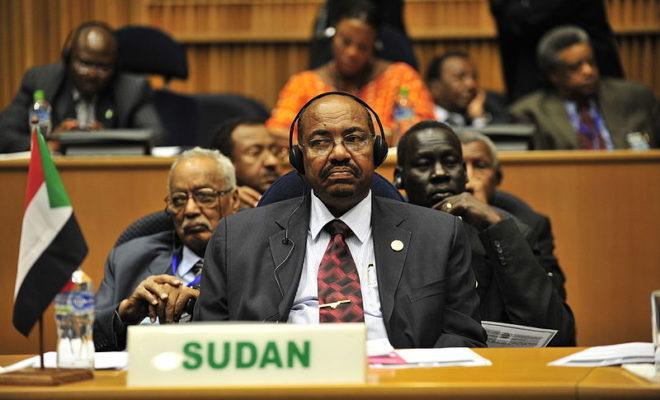

The US first imposed sanctions on Sudan more than two decades ago. By 12 July 2017, the administration of President Donald Trump must decide whether to permanently lift some of these. This is not an easy decision, but it is the better, although imperfect, choice.

After decades of hostile relations, the US cautiously started engaging with Sudan’s government in 2015 on the potential for sanctions relief. Barack Obama’s administration announced a temporary suspension in January 2017 and held out the prospect of permanently repealing them if Sudan continued a series of advances made over the upcoming six months.

[Easing Sudan’s sanctions: Lifeline for Bashir or catalyst for change? ]

As outlined in a new Crisis Group report, Sudan’s government has made important progress in five key tracks, as required by the process. This includes cooperation on counterterrorism, and with the US-backed counterinsurgency efforts against the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA). It has also ended “negative interference” – support for armed groups – in South Sudan. But progress has been less apparent in improving humanitarian access and ceasing hostilities in the “Two Areas” (South Kordofan and Blue Nile) and Darfur.

Many see the lifting of sanctions as a reward for an autocratic and repressive government. But not lifting them could discourage further cooperation and lead to a reversal of the advances made. If it repeals the sanctions, Washington would retain important leverage over Khartoum, including targeted sanctions on individuals associated with the Darfur conflict and Sudan’s designation as a state sponsor of terrorism. These could be used as leverage to push for greater change.

Sudan’s long history of sanctions

The US first imposed sanctions in 1993 with its designation of Khartoum as a State Sponsor of Terrorism. At this time, Sudan was harbouring US-designated terrorist groups and individuals, including Osama bin Laden. Trade and economic sanctions followed in 1997 and 2006 with Khartoum’s brutal tactics during counter-insurgency operations in Darfur and against the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement/Army (SPLM/A) in the south, also seen as a major problem for US-Sudan relations.

Following Sudan’s consent to a referendum on the self-determination for South Sudan in 2011, the Obama administration offered to review Sudan’s sanctions regime. But continued fighting with Darfur and in the Two Areas halted such efforts. Although justifiable at the time, keeping sanctions in place had grave implications for the relationship between Sudan and the US and reinforced mutual mistrust.

Sudan’s progress

The US will make its decision on sanctions after measuring progress against the five tracks: cooperation on counterterrorism; addressing the LRA threat; ending negative interference in South Sudan; ending hostilities in domestic conflicts; and improving humanitarian access.

With regards to the counterterrorism cooperation, Sudan started working with the US shortly after the terrorist attacks from 11 September 2001 and has, with some fluctuation, continued since. Khartoum is also believed to have distanced itself from the LRA and it recently showed willingness to cooperate to eradicate the group.

On South Sudan, Khartoum has refrained from providing significant military support to armed opposition groups. Given the continuing instability and danger of a return to famine, this remains a major priority of the US in the region. However, if Khartoum believes that South Sudan is not doing enough to stop Sudanese rebels from operating within its borders, or is seen to be channelling support to them, it could feel threatened and decide to interfere again.

More problematic are the final two tracks: refraining from military offensives in the Two Areas/Darfur and humanitarian access. Following the announcement of several unilateral ceasefires, there has been little fighting in the Two Areas and Darfur since January 2017. Given that Sudan has refrained from offensive actions, the government seems to have made progress. But the security situation in both remains fragile. Without a political solution for the underlying conflict, a ceasefire is neither sufficient nor sustainable.

[Amid silence, atrocities in Darfur have restarted]

Humanitarian access has suffered for decades in which Sudan has sought to block or manipulate aid organisations and there is a legacy of distrust between the government and humanitarian officials. A December 2016 step by Sudan’s Humanitarian Aid Commission (HAC) to establish a clear framework for the relationship between the government and humanitarian partners is a meaningful step forwards, if it can be fully implemented. According to international organisations there is at least some improvement in the general operating environment. But despite some progress, access continues to be restricted in many areas. It remains to be seen whether these first steps will yield greater and much needed progress.

Re-imposing, suspending or repealing?

Sudan’s progress remains fragile and limited. Bad governance continues as the regime engages in political repression and violates human rights. Many non-governmental organisations and human rights activists therefore call for the re-imposition of US sanctions. They say that a permanent lifting would not only reward the autocratic regime, but also incentivise it to do just enough to keep sanctions lifted without carrying out real change. Others argue for an intermediate option. As Khartoum has made partial progress, sanctions should be suspended for another period of six months to further test the goodwill of the Sudanese government.

While both arguments are valid, the progress made by Khartoum needs to be acknowledged. Indeed, several countries including the Gulf States and Israel are encouraging improved US-Sudanese relations, which serve their own geopolitical interests. Following an improvement of relations between Sudan and the EU due to cooperation on migration, key EU members such as the UK, Germany and Italy, back sanctions repeal as well.

In addition, sanctions as they existed before January 2017 were not having the intended effect. They hurt ordinary Sudanese people disproportionately, while the government became adept at surviving them. Since sanctions relief was activated as an incentive for better behaviour, real – albeit moderate – progress has been made.

Ultimately, suspending or re-imposing the sanctions could not only discourage any future progress, but also jeopardise that which has already been made. It might empower those in Khartoum who argue that restraint is not paying off and that a military solution for internal conflicts is necessary. It would confirm the belief that Washington has a history of moving goalposts in issuing demands and it would erode the recently built up trust.

Even if the US were to repeal the sanctions, the option of re-imposing them would remain, should Khartoum backtrack on its current commitments. Other important sanctions are also still intact. Thus, by repealing some sanctions, Washington would have the leverage and credibility to keep pushing for broader reforms.

Opponents of this process are right that the Sudanese government needs to do far more to win full international acceptance. But repealing the sanctions is the most pragmatic approach to try to push for more, a first step along a road that would otherwise be blocked.

The International Crisis Group ,by its own admission ,played a leading role(together with a certain Washington -based lobby which is too well-known to name)in calling for Sudan sanctions.It is now one of the voices of reason that recognise the substantial changes in Sudanese policies.The International Project that hoped to lead all Arabs and all Muslims from Khartoum against the West has gradually but emphatically been dropped.The Sudan is now ruled by a coalition of moderate forces that are keen to cooperate with all states (unless prevented by sanctions as is the case of relations with the US).The Sudan is a relative pillar of stability in an unstable region as the whole world is beginning to acknowledge.The EU’s Khartoum Process was a step in the right direction.The UK’s declaration that there are no British sanctions on the Sudan was an important step because the UK knows the Sudan very well.The complete lifting of US sanctions will also restore credibility to US policy -making.It should be followed by removing the Sudan from the Terror Sponsorship list and helping with debt relief.The ICG current stance is laudable ;but more needs to be done to support the Sudan.